Did Scraps of Fabric Lead Slaves to the Underground Railroad?

[Originally published in Aug/Sep 2005 issue of Canadian Cowboy Country]

By Ann Chandler

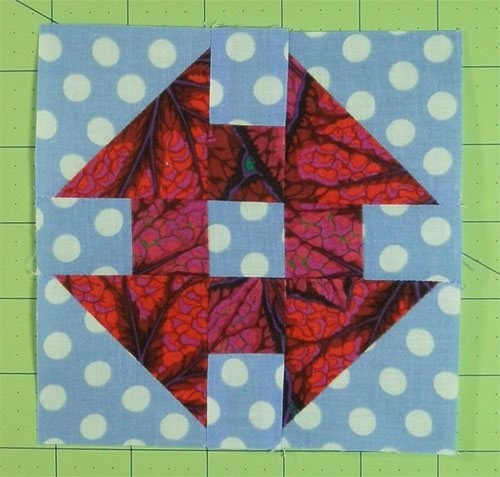

On a warm spring day in May 1854, a colourful quilt hangs out the window of the slave quarters on a plantation near Charleston, South Carolina. Few pay attention. Just the seamstress woman airing her quilt. Its cheerful Monkey Wrench pattern is not particularly significant — the mistress of the plantation has seen many. But for several of the plantation’s slaves, it’s their first signal. That night, they furtively begin gathering some precious tools — a knife, a candle, a compass — and stash them beneath the floorboards, waiting for the next coded message in their preparation to escape to freedom into Canada.

Or so legend has it.

Hidden in Plain View (Doubleday 1999) written by Raymond Dobard and Jacqueline Tobin, caused a stir amongst scholars and collectors when it related a story about a complicated secret code of quilt patterns, now commonly called the Charleston code, being used as a means of communicating signals to American slaves seeking to escape to Canada via the Underground Railroad — which was not truly a railroad, but a metaphor for a series of safe houses strategically positioned along two main routes from the slave states to several free states, and into Canada.

The book was based on an oral history told to Tobin by Ozella Williams, an

African-American quilt-maker, who claimed the secret of the code had been handed down through generations and entrusted to her. The code consisted of a series of ten different quilt patterns hung out consecutively, the names of their patterns functioning as metaphors. In the tale Williams told, she related this code:

“The Monkey Wrench turns the Wagon Wheel toward Canada on the Bear Paw’s trail to the Crossroads. Once they got to the Crossroads they dug a Log Cabin on the ground. Shoofly told them to dress up in cotton and satin Bow Ties and go to the cathedral church, get married and exchange Double Wedding Rings. Flying Geese stay on the Drunkard’s Path and follow the Stars.”

Having been taught the specific hidden meaning of each pattern, potential escapees were expected to memorize the messages the displayed sequence of quilts contained in order to follow the instructions for their journey. Even more complex, some had double meanings — a grid of stitches may have acted as a map, or specific colour may have denoted the location of safe houses. When the last quilt was hung, it signalled the time to begin the journey.

The theory is not a new one. Many adults today will tell you that the legend of a secret code was told to them as children. But oral history and oral memory often have little way of being substantiated with written records, especially when the participants were illiterate and secrecy meant the difference between life and death.

Created from a necessity for warmth, now considered a symbol of North American folk art, the humble quilt has a social and cultural history that stretches back hundreds of years in North America. When pioneer women gathered to exchange quilt patterns, they spawned many new friendships and established a sense of community. Quilts were sewn by brides-to-be in preparation for marriage. Birth quilts were sewn to honour the birth of a child. Mourning quilts were sewn to remember a loved one lost through death.

Fabrics for early Canadian quilts were often brought from Europe or the United States or were made by hand before the birth of Canada’s textile industry. Women on the lower economic scale used worn-out clothes and household linens cut into small pieces. These lovingly made quilts were well used and worn out long before there came an interest in documenting them, and few exist today as examples. The earliest quilt found in Nova Scotia dates from the early 1800s and is made from homespun wool and worn clothing. The Victorian era, with its luxurious fabrics, created a surge of “crazy quilts” made with scraps of rich silks, brocades and velvets juxtaposed in no particular pattern — hence the title “crazy”.

Unlike the lavish crazy quilts, utility quilts – not made to be aesthetic, but merely useful — were stuffed with lumpy wool or old blanket pieces, like the “soogan” made in the southwestern United States for cowboys and herdsmen as part of their bedroll. Still others were made from curious fabrics. In the hard times of the 30s, quilts were sewn from feed and sugar sacks; in the early 1900s tobacco companies placed square fabric inserts bearing pictures of animals, birds, flags, and portraits of military leaders inside their packages to be collected and traded. Several unique Canadian quilts made from these patches still exist today.

Dating quilts can be a tricky business. Some quiltmakers were generous in their identification, embroidering the year on their quilt. This is true of some commemorative quilts, like the Confederation Conference quilt made from cuttings of dresses worn by the ladies of Charlottetown to the balls and galas at the Confederation Conference and carefully embroidered with the date 1864. Some even went so far as to embroider their name on the quilt, like Annie McClung, who purportedly sewed hers from the clothing of family members — including the famous Nellie. Signature quilts, popular during the 19th century, sported a collection of signed blocks that frequently included the date.

With no personal markings, however, experts must rely on clues like dating the fabric, which may be misleading, or the type of bating used. Canadian quilts were often batted with wool, and sometimes even silk, but early American quilts, especially in the south, were usually batted with cotton.

Whether functional or commemorative, the making of quilts has endured through the centuries, enjoying a revival in the time-stressed retail world of today. Most Canadian communities boast a quilters club or two. Hundreds of different patterns adorn today’s quilts, a significant number of them the same or adapted variations of those brought by pioneers and handed down through generations. Common patterns may be known by more than one name, making the roster of pattern names much longer than the inventory of actual patterns.

And it wasn’t always women who did the quilting. Eighty-six-year-old Ann Gow, who lived in the Gaspe region as a child, treasures her family heirloom quilt — made by her father. A fisherman, he busied his idle hands in the winter by quilting and knitting woollen underwear and socks.

But the legend of the Underground Railroad quilts had been circulating long before the publication of Williams’ story. Gow, and many of her fellow quilters of the Century House Quilters group in New Westminster, B.C., who are transplanted easterners, remember hearing of the secret quilt code when they were young. But Doris Bowman, a textile expert with the National Museum of American History, says, “There is no concrete evidence to support the theory.” The tale told by Ozella Williams, who passed away shortly after the book was published, was refuted by a well-known U.S. authority on Underground Railroad history, Giles R. Wright, who said the story lacked corroborating historical evidence. He questioned, among other things, that slaves would even need a secret quilt code — could they not just speak in private when they were alone?

The debate continues. It’s a fascinating tale and we may never know how true it really is. Like most oral histories, the decision to believe is left up to the listener. But it sure makes for good storytelling around the fire.

Ann Chandler is a freelance writer and anthropologist living in New Westminster, B.C.