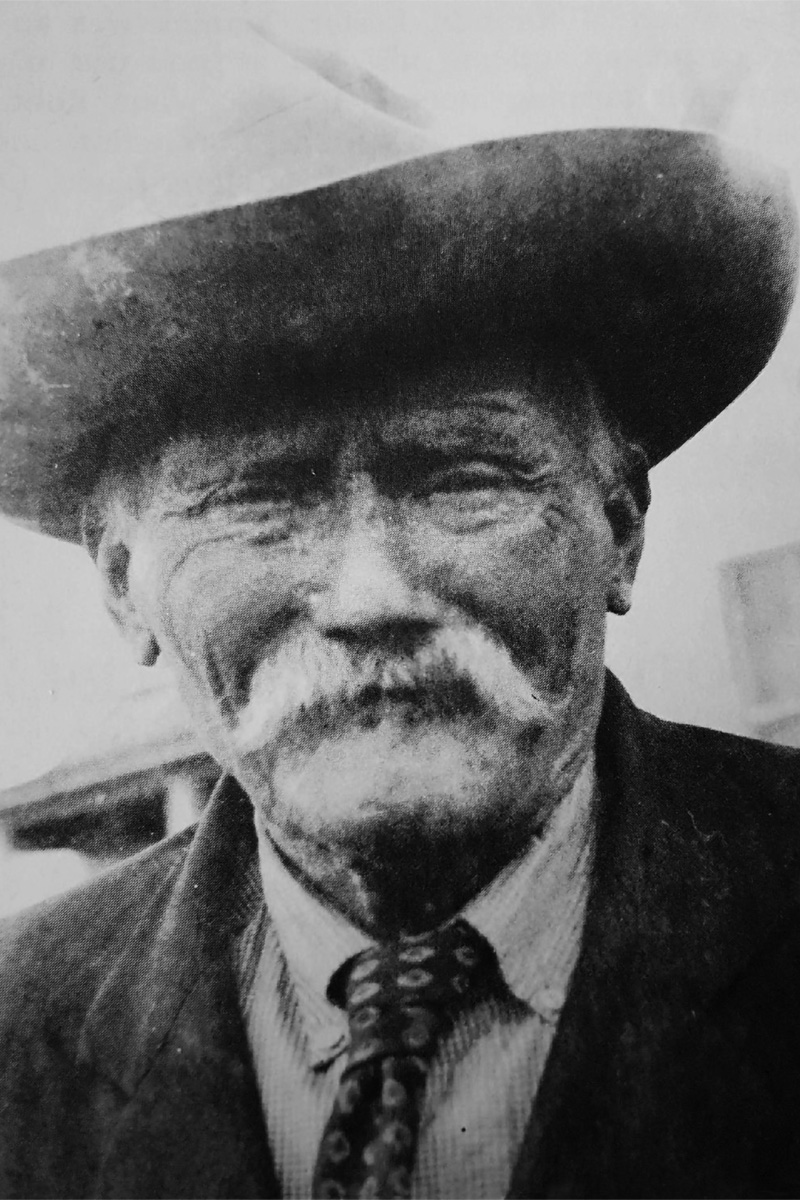

His name was William Browning Greathouse, and in the Neutral Hills of Alberta he is still a legend. Born in Arkansas on March 31, 1866, Bill grew up in San Saba, Texas, a cattle shipping center known for violence during the post Civil War era.

Comanche raids, vigilante actions and outbreaks of typhoid were more common than law and order, but by the time Greathouse turned sixteen, he had cowboyed on ranches in Texas and New Mexico and become a top hand. He eventually kept moving northward on cattle drives, and by Christmas 1899, he was in Medicine Hat and working on ranches in southern Alberta.

In 1902, the Texas-based Wilkinson-McCord Ranch hired Greathouse as round-up boss to move their cattle north to the grasslands in Alberta. In the spring of 1903, 3,680 head of their cattle and 200 horses were loaded onto eight trains at Canyon City, Texas and shipped to Miles City, Montana. They were then trailed about 1,000 miles to Sounding Lake, Alta., covering about 15 miles per day. They arrived at Sounding Lake late in the season, and the weather proved unrelenting. The continuous rain had formed a huge bog at the confluence of Sounding Creek and Lost Creek. Greathouse and his team were able to swim the horses across, but the cattle had to be trailed around the bog. Their hooves churned the trail into mud, so the crew had to cut willow branches to make a corduroy road that would allow the wagons to follow. In 1906, Greathouse was still working for Wilkinson-McCord in the Neutral Hills, and on November 16, temperatures plummeted as an intense three-day blizzard struck. Cattle were still out on the range as three feet of snow fell on the range cattle and the winds topped the drifts with a thick frozen crust. Hungry, thirsty cattle drifted with the wind as the ice crust cut their legs. The cowboys (dressed in buffalo coats and coyote fur foot wraps) tried to drive them in closer to the haystacks, but the exhausted cattle would not move far. They brought hay to those they could reach and kept chopping water holes in the frozen ponds. Warren LaRoche and an unnamed Wilkinson-McCord cowboy froze to death in the storm. Greathouse, knowing the same thing could happen to him, kept some money with a note that read, “kase I kick the bucket, fix things up.”

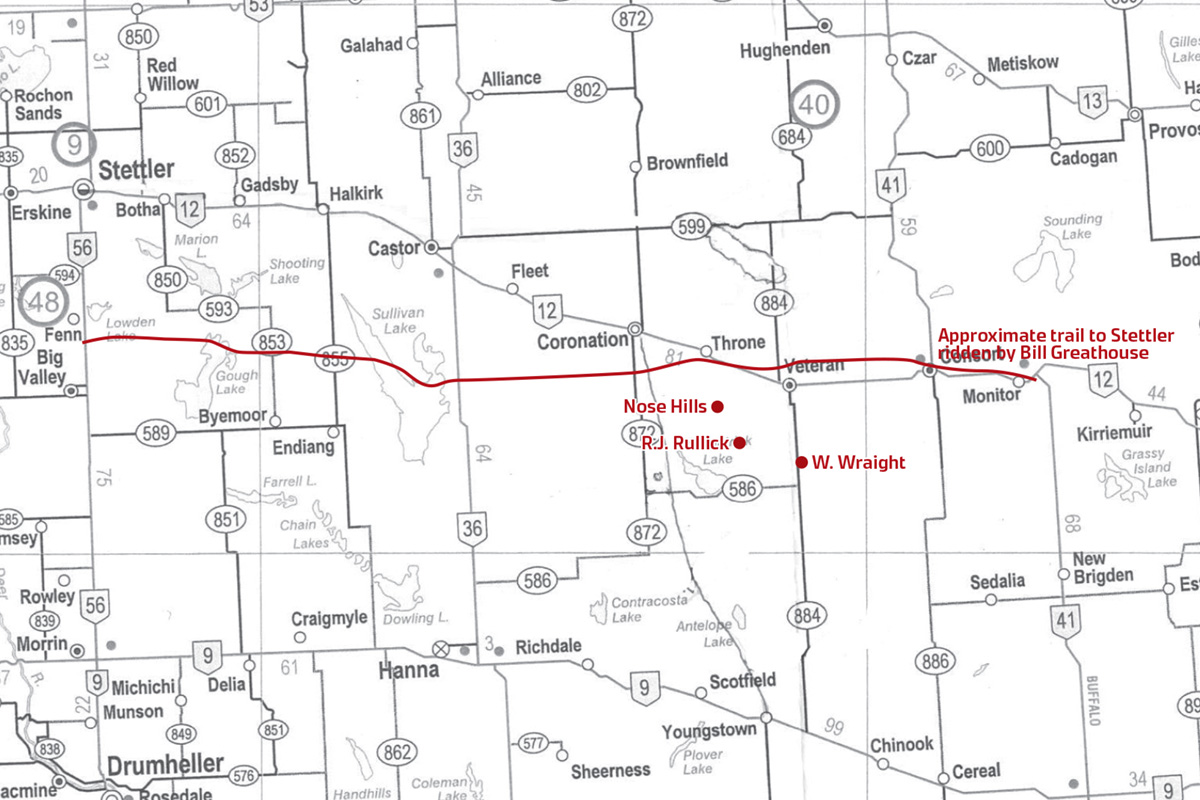

During this same storm, Mrs. Ellis, the Wilkinson-McCord ranch cook, fell gravely ill. The nearest doctor was over 100 miles away in Stettler. Against all advice, Greathouse saddled up his strongest horse and rode off into the driving wind to get help. He rode from ranch to ranch, breaking trail on foot where necessary and changing horses at each ranch. Arriving in Stettler exhausted and frostbitten, Greathouse described the ailing cook’s symptoms, and the doctor gave him some medicine. Greathouse rode back the way he came, once again relaying horses. Pinned inside his coat was a note that gave his name and who the medicine was for in case he froze to death. He never stopped to rest, and the grueling round trip took 36 hours. Mrs. Ellis recovered.

When the Neutral Hills School opened, the folks celebrated with a dance. A collection was taken up and offered to Greathouse for his good deed. The tough horseman refused the money and, instead, claimed every dance with the schoolteacher. Greathouse wanted to raise horses, so he bought 300 head and some cattle, settling on the east side of Sounding Lake. Beef prices were very high in 1919, and the following spring, feed was in short supply in surrounding areas but still abundant at Sounding Lake, so Greathouse gambled. He borrowed $10,000 from the bank and bought yearling steers for $60. But the short-lived, post-war boom collapsed, and he struggled to pay his debt and taxes. By 1921 he cowboyed again for much-needed cash.

The dry spring of 1923 forced Greathouse to sell cattle at two cents a pound, and he trailed the remainder with his horses to Meadow Lake, Sask., then towards North Battleford, spending most of his cash on feed. He had become a nomadic stockman, moving to wherever there was free range. Greathouse camped with his stock, even at below freezing temperatures, in a brush shelter with just a campfire and a few blankets. When the mercury plunged, he sheltered in an abandoned cabin or old schoolhouse. He sold off all his cattle, and in the spring, he trailed his horses back to Sounding Lake, but the area was drought-stricken.

The following year, he drove his now 200 horses into the Maidstone District, drifting along the North Saskatchewan River to the Eagle Hills. His horses, however, kept getting impounded, and the fines ate up his cash, so he trailed them towards some pasture near Edgerton, Alta. By this time, Greathouse was a tall grizzled man in his 60s, who would have fit well in a Charlie Russell painting. He rode a single-footing chestnut gelding with short frozen-off ears, named Croppy, that could cover 40 miles a day. Greathouse used manila grass ropes and preferred to dally. He could also hoolihan and forefoot a horse with expertise.

Greathouse’s epic ride

Bill Bonner was working at a livery in Wainwright and remembers herding horses for Greathouse in the early 1930s. Bonner noted that Greathouse’s horses were whip broke and were never tied in standing stalls in the Wainwright livery. When he slapped his chaps with a quirt, his horse would back out and come to him. Bonner also remembers Greathouse’s dry sense of humour. They lived on simple pancakes wrapped up in newspaper. By lunchtime the print had come off on the pancakes, and Bill joked that the boys could read the comics while they ate lunch.

The Canadian West was not as tame as the politicians of the time claimed, and horse rustlers were a problem. Greathouse had grown up in violence, rode mostly alone and always carried a Colt .45 revolver and a Winchester rifle for self-protection — and he knew how to use them. Poker games were common above the Wainwright livery, or wherever Greathouse happened to be staying, and he would lay his gun on the table to keep the play honest. In one game, he won $300. The cowboys stayed for the night, and the next morning when Greathouse was getting dressed, he realized his $300 was gone, so he pulled the Colt and demanded his winnings. Dazed cowboys looked for the lost money until Greathouse realized he was wearing the wrong pair of pants. His money was safe after all.

Another time when a local cowboy stole Greathouse’s Winchester rifle, he rode up to the bunkhouse porch and shot the thief’s boot heels off with his .45. The rifle was promptly returned. Bill Bonner would occasionally ask that man if he had seen Greathouse lately, but the culprit stayed clear of him.

By 1941 Greathouse had drifted to Kirkpatrick Lake and was staying in a vacant school. His old ranch buildings had been torn down for firewood, and with bank liens and back taxes there was no chance of rebuilding. He continued to freegraze and camp where he could. His horse herd had dwindled to about 85 head, and by winter he was living alone near Antelope Lake. Clearly, he needed to retire from the wandering life. By 1948 he was living in Calgary and in failing health. Bill Greathouse passed away October 19, 1951. He is buried in an unmarked grave in Queens Park Cemetery in Calgary