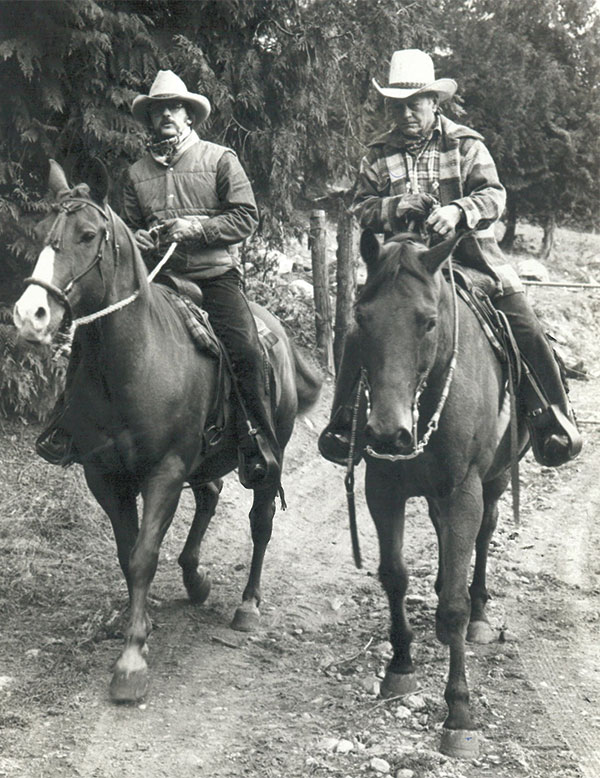

Master horseman Merrill Harrop learned much of his horsemanship from a Spanish cavalry officer and by the time I was lucky enough to apprentice to him, he was considered by the Thoroughbred industry to be one of the best horse trainers in Western Canada.

He was born in 1913 to Orliff and Mabel Harrop, who had six children and farmed six miles south of Aylesbury, Sask. Merrill was motivated to study horsemanship from riding a tough little gelding named Scot to school. Although the school had a horse shelter, the hay ran out before the day ended and Scot would buck and spin around to avoid leaving the farm. Merrill rode bareback and would sometimes lose the lard pail containing his lunch. The situation was made worse because he was born with web fingers on his right hand that made holding the reins difficult until it was corrected with surgery. Orliff had worked on the Miller Horse Ranch in Montana before moving north to farm, and he encouraged Merrill to persist with Scot. By necessity, Merrill became more interested in horse behaviour than math or history in school.

Orliff died when Merrill was 12, and the family lost the farm and moved to Saskatoon. Merrill worked at Ross’s Livery Stables and there he met Joe Tigh, an ex-Spanish cavalry officer who had been an instructor at the Spanish Riding School in Vienna. Tigh had killed another officer in a duel and, forced to leave Spain a wanted man, moved to Pike Lake, Sask. Tigh taught Merrill the riding school’s ground work techniques for starting and schooling horses.

Merrill and Joe lived in a small hut that had a dirt floor, two cots, a small wood stove and a sod roof. They ate salt pork, beans, baking soda bread and the occasional egg from a hen that would nest on Merrill’s cot.

Merrill progressed rapidly as a rider and young trainer, learning methods that avoided harshness, focusing on gaining the horse’s trust and respect. He later worked for Alec Johnson of Mozart, Sask., and Captain Stanley Harrison of Ft. Qu’Appelle, a wellknown Thoroughbred breeder. For 12 years he was a jockey in western Canada and the USA. He came out to the coast in 1939 and it was here that he met his wife, Mary. He continued to train racehorses in Vancouver and after the 1942 racing season was over, he moved to Victoria, working horses for Don Carley of the Victoria Riding Academy. He also drove the Tally Ho Coaches six-horse hitch. He started importing racehorses from The Speers Ranch in Saskatchewan, training and selling them. Some raced and others were bought by chuckwagon outfits.

By the time I began working for him in the late 1970s he was standing a stallion named Pony Soldier, starting colts and working on horses that had behavioural problems. He was 74 years old the last time I saw him gallop a racehorse at the track.

Working for him was an education in old school ethics and his word was his bond. I had graduated from Meredith Manor Equestrian College in West Virginia and when we shook hands, he said with a grin, “So you’ve been to college eh? Welcome to the school of hard knocks.” And he was right. Learning to correct horse behaviour problems required a special set of skills and perceptions.

He was fair with horses and owners alike and he applied the same principles to life that he did to training. He believed that people and horses needed a combination of insight, good judgement, light hands and relentless patience. He was a demanding boss but fair and expected a full day’s work for a day’s pay, both from his workers and his horses. He often said, “Wet horse blankets make good horses,” alluding to sweat from hard work. He was a stickler for details about a horse’s behaviour and to paying attention to one’s equipment.

We worked in good weather and west coast rain. “This is what they are paying us for,” he’d say. As the water ran off the brim of my hat he’d comment, “Horses and riders won’t melt in the rain.”

He had a way of teaching you things even when you didn’t think you were learning anything, and he did not offer a lot of praise. “You ought to know when things are going right,” he would say, but he was quick to reward his horses, and remind others. “Now reward that horse, remember they work for no wages, ask for no wages, and know of no unions.”

In 1978, he wrote a short book entitled, Schooling the Young Horse and another in 1991, Saddles and Silks-60 Years of Breaking and Training Horses.

Merrill passed away on Nov. 23, 1996, and one of the ways he is remembered is by a trail named after him in John Dean Park north of Victoria where we spent many hours riding. I will always remember him as having been an excellent horseman and mentor.

As for the horse named Scot that started Merrill on his career, he settled down after Merrill’s dad used him to plow summer fallow. After that, going to school wasn’t such a bad idea.