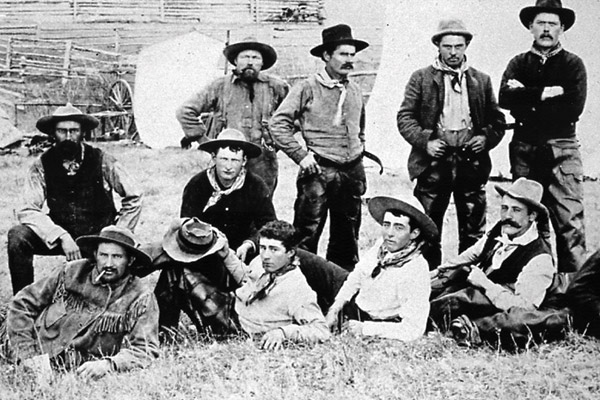

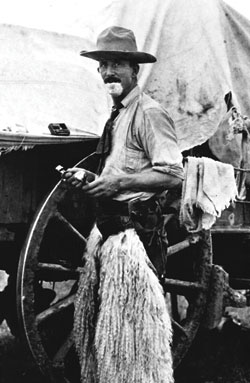

Shaving on the Range When the West Was Wild

Hot water was scarce, you could give yourself a nasty cut, and in the dry prairie wind the soap could cake on your face like plaster. Conditions on the 19th century cattle drives made shaving with a straight razor so challenging that many cowboys favoured full beards, Van Dyke goatees, or imperial moustaches. In fact, facial hair depended as much on protecting the vulnerable parts of your face as it did on style. A straight razor, nicknamed a cut throat, required skill to avoid blood loss, and skill was only acquired through practice with the razor?—?a cowboy’s Catch-22.

Choosing the correct razor was important. You had to have one that fit in your hand comfortably and to this end, razors varied greatly in their width, length, balance, temper, grind and finish. As a novel distraction, some were inlaid with brass or decorated with engravings, while their cases and handles could be fashioned from bone or ivory. Others were as simple in their appearance as they were in their functionality, and came out of the box with a basic wooden handle. Fancy or plain, a successful outcome had much to do with the skill of the hand wielding the blade.

Keeping a very sharp edge on a razor was a necessity, even though the steel was excellent quality German Solingen or English Sheffield. Razors often came in a matched set of seven because it was believed that steel fatigued from use, and an edge should not be worked more than once per week. Of the seven blades, the Saturday razor had a special notch for moustache trimming.

A shaving kit also included sharpening devices and you needed both a strop and a hone to keep the razor useable, so that it didn’t feel like your face had been harrowed after every shave. Hones were natural abrasive stones with a different coarseness on either side and were called Belgium or water hones. To smooth out the razor after honing, the edge had to be stropped with a piece of prepared leather called Russian cowhide. Actually, this was often horsehide that had leather soap worked in as a conditioner. You tested your honed razor by passing it over your thumbnail and your stropped razor over the moistened gall of your thumb.

A shaving mug was also needed which was usually a straight cup with a soap dish attached, or a rest for the brush on the handle, and some even came with a spout so they resembled a coal scuttle. The soap itself was a round wafer, like a small hockey puck, that could produce a rich lather using a brush made of boar’s bristles. In theory, a shave should be completed in 14 strokes from four basic positions. In reality, theory and practice are usually different, so it might take a couple of extra swipes to get the job done. Shaving lotion was bay rum or real vanilla extract. Out in the open, the wind had a tendency to dry the soap quickly producing a dilemma?—?you needed to take your time to avoid cutting your throat, but the lather had to be kept moist so it didn’t flake off under the blade. If that wasn’t enough aggravation in your day, all the equipment made a cowboy’s shaving kit a cumbersome addition to bedrolls or saddle bags.

Those who were deterred from applying cold steel to face, and didn’t mind looking like a cast member from the movie Culpepper Cattle Company, could go to town and get a professional shave from a barber. Depending on the era and locale, barbers could provide various and sundry services including baths, bleeding with or without leeches, dentistry, wound dressing, and cauterizing. They might set simple fractures if a doctor was not available, and even removing bullets was not out of the question. In fact, the once familiar barber pole was originally just red and white stripes?—?for blood and bandages?—?with the blue stripe being added as a patriotic symbol by American barbers at a later date. There was no formal training for barbers until 1893 when A. B. Maber opened a barber school in Chicago. For the most part training was undertaken via apprenticeship, so the success rate of some procedures without formal training was sometimes sketchy at best. New technology was needed to minimize cowboys’ face wounds so the Wilkinson Sword Company marketed safety razors in 1890 and K. Gillette came up with throw away blades in 1902.

Some mark the passing of the Wild West era with the end of the open range and the coming of barbed wire fences. Others denote that it was the arrival of cattle liners and feedlots that ended the Golden Age of the West. However, there are still others with less than steady hands, who claim that the Wild West was really ended by Wilkinson and Gillette and the demise of that old cowboy nemesis, the cut throat razor.