Capturing Canada’s History

By Tim Lasiuta

Calgary photographer Alexander Ross was a man at the right place and time.

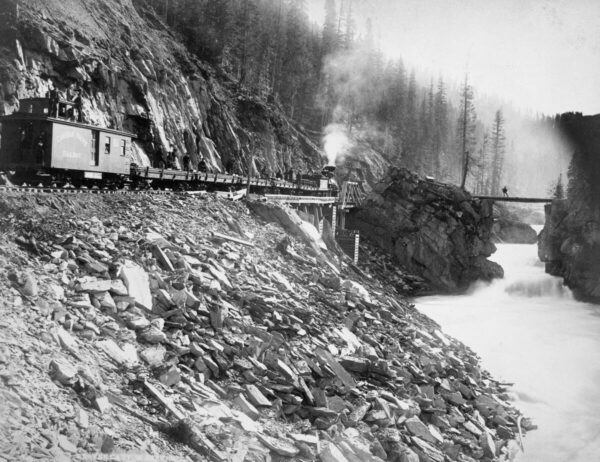

On November 7, 1885, at precisely 9:22 a.m., in Craigellachie, B.C., William Van Horne and Director Donald Smith presided over a muted ceremony that unified the Dominion of Canada. Of that momentous occasion, Van Horne declared, “All I can say is that the work has been done well in every way.”

The same could be said of the iconic photo series Ross took of the event.

Lord Strathcona drives the Last Spike to complete the Canadian Pacific Railway on 7 Nov 7, 1885.

Toronto photographer Cornelius Soule, who had been assigned the opportunity, did not arrive. Ross ‘happened’ to be present and captured the photo that helped define his career.

Alexander Ross came from humble beginnings. His family arrived in Canada in 1773, and he was born in 1851 in Pictou County, Nova Scotia, to Hugh and Ann (McLeod) and was one of seven children.

He started an early photography studio out of the family home in the 1870s, later moving to the Pictou waterfront. When his brother John joined the business, A.J. Ross and Company, he changed the name to Ross Brothers Photography. The pair opened studios in New Glasgow, Truro, and Charlottetown, winning first prize in an Exhibition in Truro in 1878.

Despite their success, the pair dissolved their business, and Alexander went to Illinois in the early 1880s and married Mary MacArthur in 1882. The Manitoba Archives report that he started Best & Brother, which allegedly ran from 1882–83. According to the Glenbow Museum, the couple moved to Calgary and started a horse ranch in 1883 on what is now known as Spy Hill. The following year, he and Mary moved to Winnipeg, where they joined brothers Hector, John and Thomas. Along with John Best (again), he formed Ross, Best and Company and became known as “portrait and landscape photographers.” (1884-87)

Alexander Ross self portrait date unknown.

(NOTE: While researching this article, there is a discrepancy in timelines. It would be greatly appreciated if any reader could help clarify this.)

During the railway construction, it is reasonable to suggest that due to Ross’ reputation as a photographer, he was contracted to photograph the line’s progress.

With the thrust of a sledgehammer, the last spike was driven by Smith and with the snap of a shutter, Ross stepped into the role of Canada’s photographer.

“Photographs like the Last Spike provide the visuals for the stories we tell. It is often said that a photograph is worth a thousand words,” said Historian Michael Dawe. “Therefore, having such photos extend and enrich the stories and make experiences much more meaningful.”

Upon his return to Calgary in 1886, he turned his attention to documenting life in and around the growing settlement. In addition to portrait photography, he captured the lives of the Sarcee-Blackfoot (now T’siu Tsina) and other first nations, including the Asini Wachi Nehiyawak (Mountain Cree) in studio and on the plains.

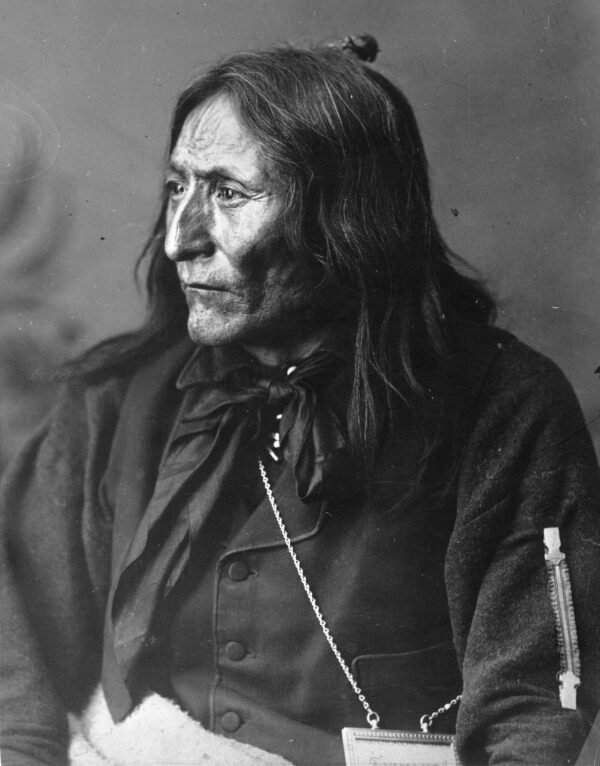

Crowfoot (1830–1890), or Isapo-Muxika, was a chief of the Siksika First Nation.

His fascination with the First Nations peoples increased, and he spent a large portion of his time between 1884 to 1891 taking photos of First Nation camp life and more traditional portrait sittings. The portraits he captured include Crowfoot, Rabbit Carrier, Sarcee woman Katie, Chief Owl, Bobtail, and many warriors, mothers and children.

“As a present-day descendant of Bobtail and elder of the Asini Wachi Nehiyawak, the value of his photographs cannot be calculated,” said clan mother, Sandra Larocque McLeod. “They are part of our history and family heritage.”

Innisfail and District Historical Society curator Anna Lenters shared McLeods’ sentiments.

“As a museum curator with Cree descent, I look at the photos and see my grandmothers’ cheekbones in the faces of the mothers and grandmothers,” said Lenters. “It is a very unique experience.”

She added that looking at the pictures makes her want to tell the real story of the people of Canada before it is lost forever.

In 1891, Ross unexpectedly closed his business, passing away in 1894 at 43.

His surviving work speaks of a man who saw his world through a lens that captured a world of stark contrast and simplicity. Posed in studio or in situ, he preserved a fleeting time struggling to reconcile dramatic change with Victorian ideals.

Today, our world views photography as disposable, yet Ross saw his work as a service to the future, who would never see live what his lens captured.

His star burnt quickly, and in his wake, he left photographic treasure for generations.

Alexander Ross is buried in Union Cemetery in Calgary