Settlement

“Some of us will not be content in heaven if we hear of a place further West.”

—Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald, 1881

The drive for prairie settlement gained momentum as unfarmed land became scarce in eastern and central Canada. Settlers looked to the huge HBC territory west of the great lakes. Industrialists proposed westward Canadian expansion, and they envisioned the movement of manufactured goods towards the setting sun and a reciprocal passage of agricultural products east.

George Brown, a prominent Toronto newspaperman and politician, enthusiastically promoted Canadian acquisition of HBC territory. By the 1850s this proposal had become a major Canadian political issue. A race developed between the British colonies and the expanding — and increasingly more powerful — U.S. In central Canada, political deadlocks would be solved by Confederation and that could only be sustained by western expansion. The key to such expansion was settlement.

With the decline of the fur trade, the HBC sold its territory to Canada in 1869 for $ 1.5 million plus some concessions. The Canadian government was so anxious to acquire — and the HBC to divest — that they forgot to get the Métis onside.

Between the Great Lakes and the Rockies the only settlement of any size was Red River, virtually isolated until the 1850s when American settlement linked it to the U.S. through American traders. Adventurous Canadians looking for land trickled in from the East in the 1860s. More and more, the fur trading buffalo hunter had to adapt to settlement and agriculture. The U.S. agitated for annexation of the area. Canada pressed to extend Confederation and the Métis were caught in the middle. They were never told how they would be governed or represented. The Canadian settlers boasted they would take over Red River, the Métis wondered if traditional land ownership would be honoured. A fight was brewing.

Under Riel’s leadership, a group of Métis stopped the work of a Canadian survey party and prevented the new governor from entering the settlement ahead of schedule. Riel took over Fort Garry and set up a provisional government. Afraid the U.S. would use this as an excuse to annex, Macdonald negotiated with Riel. In 1870, Manitoba became a Canadian province with full representation in Parliament and the Senate. Métis land ownership was recognized, but Riel had made a grievous error; he had executed a belligerent Canadian named Thomas Scott. In Ontario Riel was a murderer and in Quebec he was a hero. To keep Ontario voters appeased, Macdonald sent soldiers to Red River. Riel escaped to Montana and became a U.S. citizen. Many Métis drifted west but the problems they faced in Manitoba arose once again 15 years later.

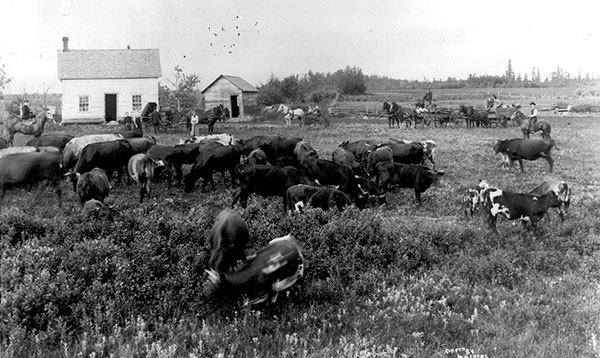

In 1881, Senator Cochrane drove 3,000 cattle into the Bow River area and for a time, about a dozen corporations controlled most of the grazing land in the southern parts of Alberta and Saskatchewan. But some of the most stable ranching operations continuing on to the present day began as family owned homesteads in the late 1800s.

By the mid-1880s however, settlers were migrating south to the U.S. and new immigration had become almost non-existent. The stalled economy was at the heart of the discontent. The price of wheat and beef had fallen while the cost of shipping caused by the tariff policy had risen. There were proponents for annexation to the U.S., and the editor of the Edmonton Bulletin suggested more could be gained by rebellion than negotiation with Ottawa. Even some non-Métis leaders were asking Riel to return.

Métis farmlands were once again threatened and First Nations people were disillusioned with government policies. In March of 1885, Riel’s second rebellion began. The army came West and for a short time, the fighting was furious and bloody but unsustainable by the Métis. Riel was taken prisoner in May, tried for treason in June — even though he was a U.S. citizen — and hanged November 16. In Manitoba and Quebec there was talk of separation. Macdonald lamented that every issue facing the new country threatened to tear it apart — a characteristic of Canadian history to this day.

World economic conditions improved as American and European markets demanded more produce and shipping costs declined with better technology. Once again the key to maintaining the continued expansion of confederation was settlement in the West and the settlers were encouraged to immigrate via the CPR.

The Canadian Homestead Act or Dominion Lands Act from 1872 until 1918 aimed to encourage settlement in the West. The Canadian government had Clifford Sifton organize an advertising campaign in the U.S., Britain and Eastern Europe, recruiting settlers that between 1897 and 1913 added over 1.25 million people to the West. Sifton was looking for new citizens that came from “ten generations of farmers.” The settlement of the West would prove to be the keystone that would lock confederation together in a viable union that Alberta and Saskatchewan entered as provinces in 1905.