Barbed Wire Strung Together the First Telephone System

By Duane Gray Migowsky

Due to southwest Saskatchewan’s geographic location and sparse population, we realized generations ago that if we want something done, we have to do it ourselves.

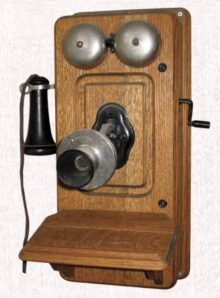

One of our great do-it-yourself ideas turned barbed wire fences into a communications network. Barbed wire, considered not very neighbourly in the last days of the open range, in this instance helped neighbours to communicate. The top strand of the barbed wire was used as a phone line in what was known as the “fence phone.”

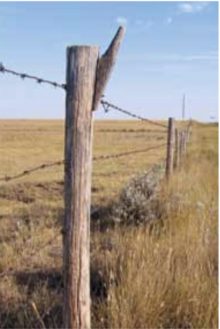

Harry Opsal, who was in charge of the PFRA Bull Station in the Bitter Lake Pasture 15 miles north of Maple Creek, explained how porcelain insulators were used to attach the wire to each fence post. Tall poles were attached to each gate so the wire could be strung over the gates without breaking the circuit.

He recalls how Johnny Smith instigated the setting up of this first communication system and how volunteers connected their community of 10 original subscribers. In the early 1950s, Ray McIntyre got poles out of the Cypress Hills, scrounged some line from somewhere and built a telephone line from Maple Creek to the junction of Highways 1 and 21, five miles to the north, where he built a service station and cafe.

Back then, Harry and Leonard Keayes – whose land bordered the Bitter Lake Pasture – built a line from the Pasture to connect with the line to Maple Creek. Harry acted as “lineman” and hooked up modern phones for anyone along the line.

The line to Maple Creek was connected to the Pasture manager’s home. A barbed wire fence phone was strung to the extension camp (known as the sheep camp) so the pasture manager could talk to his rider – who reportedly didn’t answer most of the time. They also wanted to run a line to the Big Stick Pasture, but that pasture manager didn’t want anything to do with any newfangled telephone.

It was at this time, says Harry, that things got a little crazy. There was only one line – known as a “party line” – and there were too many people connected to it. The line was always busy.

Proper etiquette dictated that you pick up the phone to see if the line was busy, before you cranked the appropriate number of rings for the party with whom you wished to speak. “It was always busy,” adds Harry. “It was quicker to drive to the person’s place, or all the way to town, than it was to phone!”

Since the Bull Station was connected to both the fence phone system and the line to town, people would phone Harry and ask him to relay a message. “That got old pretty quick,” says Harry.

The system worked — but there were a few glitches. If the barbed wire were ever grounded — the system wouldn’t work. This could happen if another piece of wire or wet grass leaned against the wire, or even if an itchy bull took a notion to scratch his neck on it.

During lightning storms, sometimes all the phones would jingle constantly. The erratic current would render all the phones useless — and you definitely did not want to use the phone at such times, lest a bolt of lightning ended up between your ears! (Everyone has a wild story about lightning coming out of the phone and shooting across the kitchen — and the yarns get better with the passing years.)

As well, everyone along the line could listen in on every conversation. This was considered a bad feature for some, a good feature for some and an “interesting” feature for others. Eavesdropping became known as “rubbering” (presumably after the expression “rubber-necking.”)

An old rancher once quipped: “The neighbours always knew when my wife was pregnant before she did.”

One important feature was the “general ring.” This was one very long ring that indicated an emergency such as a prairie fire, a home disaster or a field mishap. It was also used to announce a social event or a branding. The general ring spread the word quickly and it was one time when it was perfectly acceptable to “rubber in” on the call.

Several of these fence phone networks were set up in south- west Saskatchewan, although none of them were connected to each other. As many as eight or 10 and as few as three or four were connected to any given system. When the communications company, Saskatchewan Government Telephones (SGT) saw fit to provide the service to the entire province rather than limiting the phone service to urban communities, the company kindly purchased many of these individual phone companies, even though they would have been rendered redundant in due course.

“I think it was about the early ’60s when SaskTel bought our phone company,” said 85-year-old Harry Opsal, as he climbed down the ladder after finishing a siding job on his house. “And the rest is history.”

As a former newspaper publisher, Duane Migowsky has always been aware of people’s desire to communicate. Believe it or not, the fence phone played a significant role in satisfying that desire in its day.