Henry Kelsey’s contribution to our nation’s history is manifold: he is regarded as the first European to see the Canadian Prairies, musk oxen, grizzly bears and the buffalo. He is credited with the first peace treaties with First Nations tribes west of York Factory. He is documented as being one of the first to search for the North West Passage (1689) and is credited with writing the first dictionary of any native language. He was also a ship captain, a governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company and an early proponent of adult education.

Yet with all of these achievements over the course of a life that spanned 57 years (1670 to 1727), he was scarcely a footnote in Canadian history. That is until 1926 when Mr. Archibald Dobbs made an accidental discovery in his library in Carrickfergus, Northern Ireland. Upon examination, the papers he discovered proved to be the Henry Kelsey journals that covered 40 years spent in service of the Hudson’s Bay Company, including records of a period from 1690 to 1692 that discussed two journeys west of Fort York to secure trading rights for the Company.

Prior to the posting of the young Kelsey, the farthest west any European explorer had been was Sault Ste Marie, and all lands west had been claimed by Jean Talon for France, despite him never having travelled through them.

According to the records, Kelsey was an adventurous young man who enjoyed the company of the many First Nations tribes in the area, spoke their language passably well, and ‘could paddle with the best of them’ and carry a pack all day, in addition to being welcome in their midst.

Kelsey began his journey west from Fort York on June 12, 1690, in the company of Cree First Nations guides, with the blessing of the Company on a sunny morning. He recorded his departure in his journal:

“Then up the River I with heavy heart

Did take my way and from all English part

To live amongst ye natives of this place

If God permits me for one two years space.”

The richly detailed journal also records specific areas and geologic zones:

“the ground begins to dry with wood

Poplo and birch with ash that’s very good

For the Natives of this place wch knows

No use of Better than their wooden Bows.”

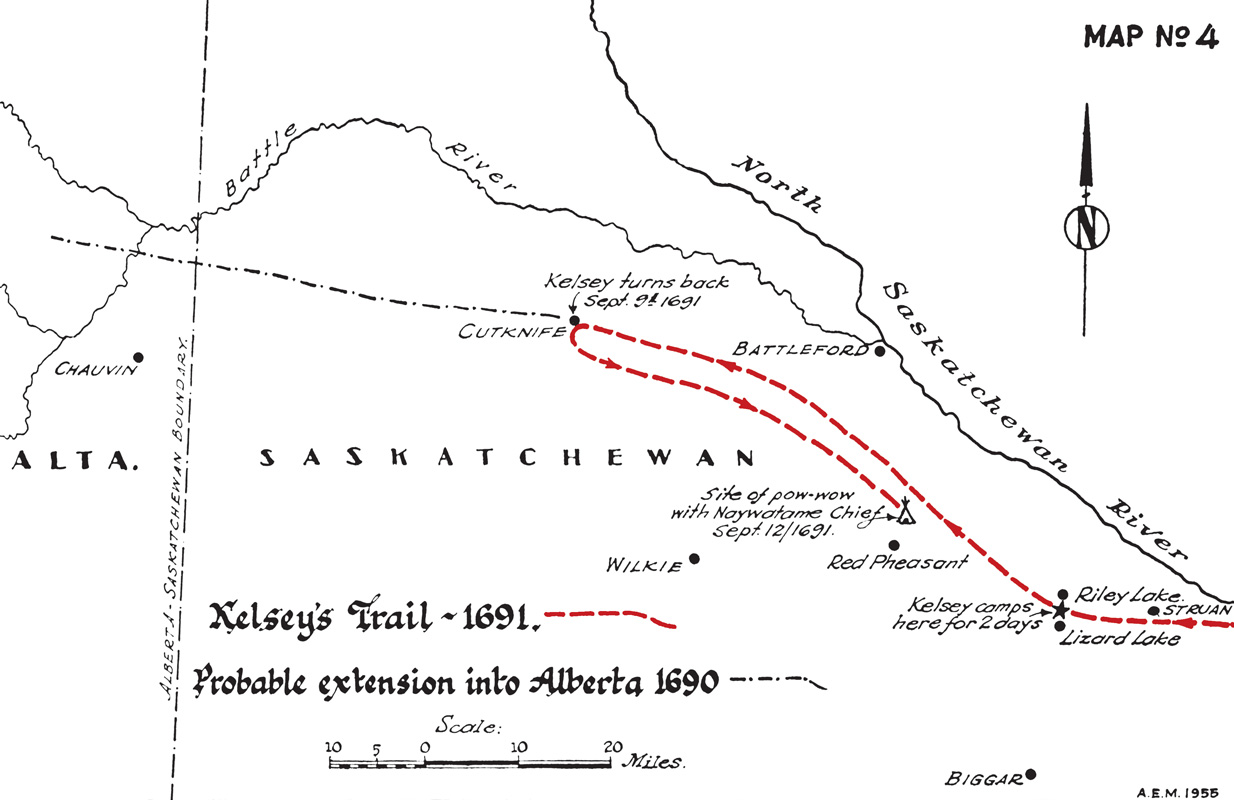

Kelsey, along with his compatriots, travelled as few as five miles per day and as many as 10 along the old trails and stopped at what is now known as Le Pas, then a Naywatame-Cree village and described it as a “neck of land.” He reached the great River of the West, the Saskatchewan (Wa Pas Kwa Yaw) and gazed on what must have struck him with awe. His journey took him past present-day landmarks, such as Nipawin (Cree for crest), Saskatoon (by the present University of Saskatchewan site), Clarkboro, and an area of “great store of buffalo,” close to the Eagle Hills (present hamlet of Struan). Kelsey travelled with the Cree and crossed into what is known as Alberta today by the Battle River, 20 km north of Chauvin.

During James W. Whillans’ recreation from 1944 to 1954, he travelled the old trails and matched journal and terrain, often conversing with pioneers who knew of the trails that lead past their homesteads and farms, and often stood on the same ground where Henday (1754) and Kelsey (1690-91) travelled. In fact, 60 years later, Anthony Henday travelled much of the same trails that Kelsey did, recording observations that shed light on the previous journey. The information gathered from both journeys explained conditions on the prairies, pre-settlement and pre-treaty.

Much of the mystery of the journal lies in its descriptive phrases, which to the eyes and ears of modern readers did not read as we are accustomed. Therein lies the romance and glamour of his journey, yet it took the discovery of the journals in the Dobbs Library and the passion of James W. Whillans to ignite the fire.

In his book, First in the West, (1955), Whillans sought to retrace the route that Kelsey took in both journeys and meticulously recorded his observations and discoveries. Other scholars and researchers, such as Dr Tyrell and the Manitoba Historical Society, have delved into his journeys, but none travelled the trail or paddled the rivers as Whillans did. While there is debate over his exact journey, there is no doubt over the significance of his journey.

Whillans passed away in 1954, hours before finalizing details of his book. Kelsey died 300 years prior and like Whillans, was unaware of the significance of his scholarly works to future generations.