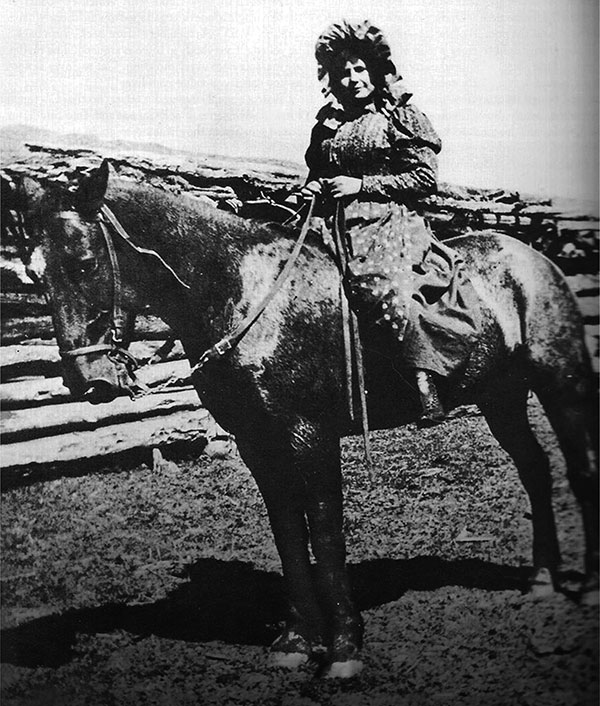

Canadian woman turned Wyoming homesteader Ellen “Ella” Liddy Watson, was later lynched by

Wyoming Stock Growers Association members. Says historian Daryl Drew; “This photo appears to

me as a hurried joke shot. The throatlatch is undone, there’s no saddle and she’s barefoot and in a

nightgown and nightcap.” This innocent image was used to discredit her as a legitimate rancher and

to perpetuate a century of misinformation.

The lynching of Canadian rancher Ellen “Ella” Liddy Watson and her husband James Averell in Wyoming in 1889 should have been an international incident. Instead, it precipitated one of the most overt cover-ups in the history of the West.

Ellen Watson (known also as Ella) was born on a farm in Bruce County, Ontario in 1861. Her friends described her as intelligent and gentle. A tall woman, she had an elegant presence and was an excellent cook, often employed in hotel restaurants. After divorcing an abusive husband, she met Jim Averell while cooking at the Rawlins House in Rawlins, Wyoming.

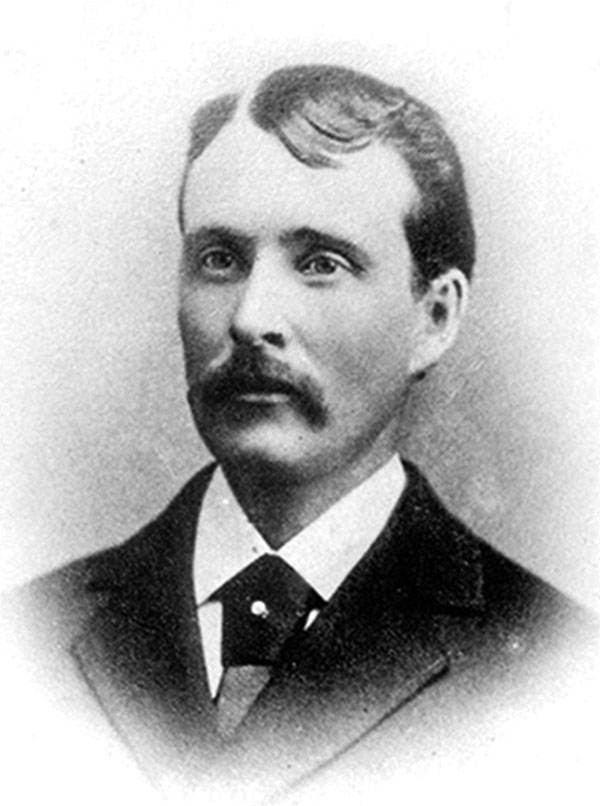

Articulate and easy-going, James “Jim” Averell was born in Renfrew County, Ontario in 1851, about 150 miles from Ellen’s birthplace. When they met he was homesteading on the Sweetwater River about one mile (1.6 km) from the Oregon, Mormon, and California Trails. There he opened a “road ranch” — a general store and restaurant catering to cowboys and to people travelling west. He hired Watson to cook at his restaurant.

The couple soon married in secret, and Watson filed for squatter’s rights under the Homestead Act on a quarter section adjoining Averell’s.

Serious trouble began almost immediately when Albert Bothwell, a prominent member of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association, found out that Ellen had filed on the land. Although Bothwell had no legal claim to the quarter, he used it as his hay meadow, plus controlled water access on this and other rangeland with 60 miles of his illegal barbed wire. Angry that he failed to get her to sell out, Bothwell tried intimidation by painting a skull and crossbones symbol on Watson’s cabin door. Unfortunately, neither Watson nor Averell took the threat seriously.

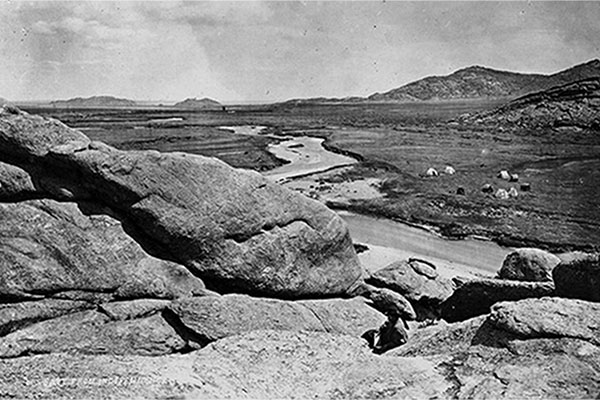

On the morning of July 20, 1889, ranchers Bothwell, Ernest McLean, Robert Galbraith, John Durbin, Robert Conner and Tom Sun tore a hole in Watson’s new fencing and scattered her cattle before forcing the 28-year-old homesteader into the back of a tandem buggy. The lynch party then found 37-year-old Averell a mile away and captured him at gunpoint. They headed down the shallow Sweetwater riverbed toward Independence Rock with their two captives.

But there were witnesses to the abduction. Two boys told Averell’s young nephew, Ralph Cole, about the events just after they happened. A young ranch hand, Frank Buchanan, exchanged shots with the lynching party and alerted the sheriff, but it was too late for Watson and Averell — the couple was already dead at the end of a rope. But Bothwell and the others knew they now had a serious problem. Questions would be asked, investigations would be undertaken and Bothwell and his conspirators could be recognized from their horses’ brands.

An urgent telegraph was sent to WSGA operative stock detective George Henderson regarding how to cover up the murders. The WSGA controlled the largest newspaper, the Cheyenne Daily Leader, and writer Ed Towse was given the job of distorting the facts to make the actions of the murderers appear justifiable.

Towse mixed Ellen Watson’s identity with a known prostitute named Kate Maxwell, concocting the story that Ellen accepted stolen cattle as payment, using the alias Cattle Kate. From then on in numerous articles, the distorted facts continued to be reprinted. By the time the event was investigated, the misinformation was deeply planted in everyone’s mind. But the conspiracy deepened. The inquest was stalled as key witnesses began to disappear, die or fall silent under Henderson’s pressure. Ralph Cole died of symptoms consistent with strychnine poisoning. Frank Buchanan, after a relentless pursuit by George Henderson, vanished. A few years later a skeleton was found with objects that identified him as Buchanan.

Time passed and none of the lynching party was ever brought to justice. Ernest McLean left the Sweetwater Valley and seems to have vanished. Robert Galbraith sold his ranch and became a wealthy banker in Arkansas, dying in 1939. John Durbin sold out and became a wealthy meat packer until he died in 1907. Robert Conner also became wealthy from the sale of his ranch and moved back east. He was later implicated in land stealing, cattle rustling and was suspected of organizing the poisoning of Ralph Cole. Tom Sun ranched until 1909 when he passed away.

Bothwell kept ranching until 1916 when he sold out his holdings. He carefully and legally acquired the Averell and Watson homesteads and had Averell’s buildings skidded over to his property on Horse Creek. Ellen Watson’s cabin was used as a one-room school house. Bothwell died in 1928 in a care facility in Los Angeles, reportedly from complications related to mental illness.

Ironically, George Henderson himself was assassinated either by a Watson-Averell supporter or by WSGA members. It is widely believed he was murdered because he could implicate his employer, John Clay, and the six WSGA members of the lynch party (as well as the Carbon County political hierarchy who had connections all the way to Washington) in the cover-up and conspiracy.

In the end, the Averell’s possessions were sold off at auction, and their property claimed by members of the WSGA — one of many events that eventually sparked the Johnson County War (1889–1893) as well as the execution of stock detective Tom Horn in 1903.

Ellen Watson and Jim Averell are buried in Natrona County, Wyoming.