Changes and Adaptations

“All is change. The cattle came from elsewhere. So did the horses.”

—When the Indians Became Cowboys, Peter Iverson

For the Sioux in Canada, the winter of 1879–80 had been long and hungry. The insufficient return of the buffalo made it clear that the old way of life was doomed. If they were aware of the westward progress of Confederation they would not have embraced it as a solution to their problems.

To a people used to roaming at free will, the way of life coming from the east was incomprehensible. It produced Canada as an emerging political entity driven by technological development in a rapidly industrializing world. Canada’s very existence was in large part an adaptation to that changing world. However, as Saanich First Nation teacher Dave Elliott stated, this rate of change had accelerated to such a degree that it “ripped his people from the age of the canoe and dropped them into the age of nuclear power in one lifetime.”

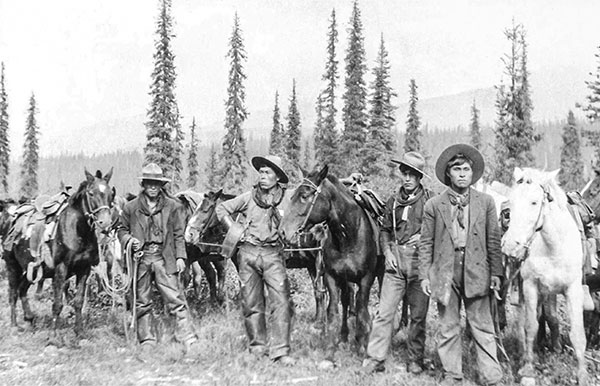

Social destabilization resulted. The First Nations were certainly adaptable as they had embraced the horse and gun in one generation. But very quickly they lost the ability to just pick and choose which new technology they would incorporate into their way of living. Following the new products heading westward was the society that created them. It would arrive in the West as a packaged deal and the products were wrapped up in a new way of living.

The new society was organized in cities which were not self-sufficient units. Everything they needed came from somewhere else. It was, in fact, the demand for beef in these industrialized centers that gave rise to cowboy culture in the first place with the huge drives in the 1860s-70s. Mass demand required mass production. When the corporate structure was applied to ranching, venture capital came from Canadian, British and American syndicates and it flowed as long as the profits did as well.

The new society was not based on self-sufficiency and independence as the First Nations society had been, but upon an interdependent network of specialized workers. As the technology became more complex, only specialists could make it and fix it, although everybody used it. Power was now centralized in corporations and distant governments, with entities like the NWMP to enforce their decrees. This new society was also highly synchronized and it created a standardized culture, served by consumers of mass produced goods that fit into a standardized set of values. This required a school system that would replicate these values with rows and rows of students in a factory-like setting, engaged in the rote learning of the skills needed to be consumers and producers.

For First Nations people this schooling process epitomized in the residential system proved disastrous. To standardize them meant to destroy the old culture by breaking continuity between the generations through an attack on language. In an oral culture, information was lost when the language that carried it was lost. With their social fabric already shattered by epidemics of smallpox and tuberculosis, their adaptive social institutions struggled to cope with the rapidity of change.

However, as Blackfoot rancher William Big Spring pointed out, there was still a place where independence and self-sufficiency were essential life skills and that was in the rural West. One could still earn a living in the new economy from the back of a horse.

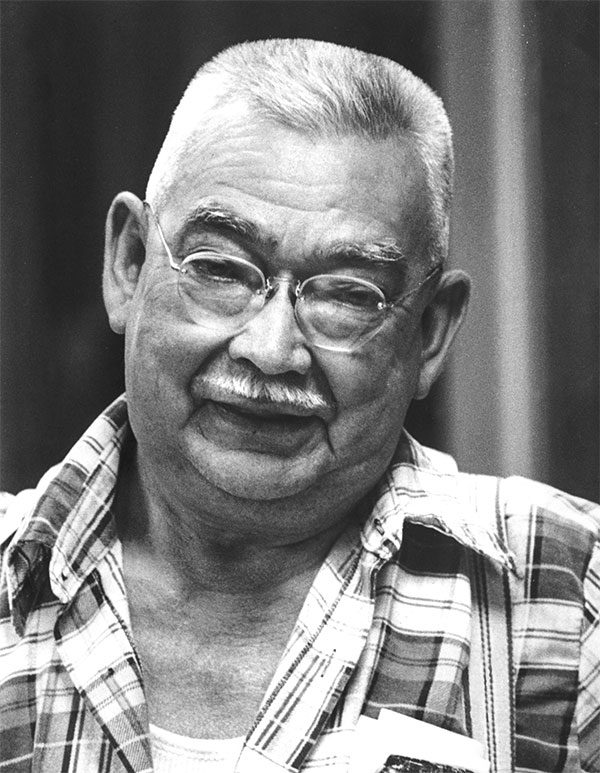

It is here that for some First Nations we might find the horse as the single factor that made ranching and cowboying a choice as cattle replaced the buffalo and the old hunting way of life. First Nations cowboys became significant contributors to the ranching industry throughout the West and rodeos developed as tests of a cowboy’s working skills. Some Native cowboys like Rufus Goodstriker, Fred Gladstone and Kenny McLean became very proficient at the skills of the sport.

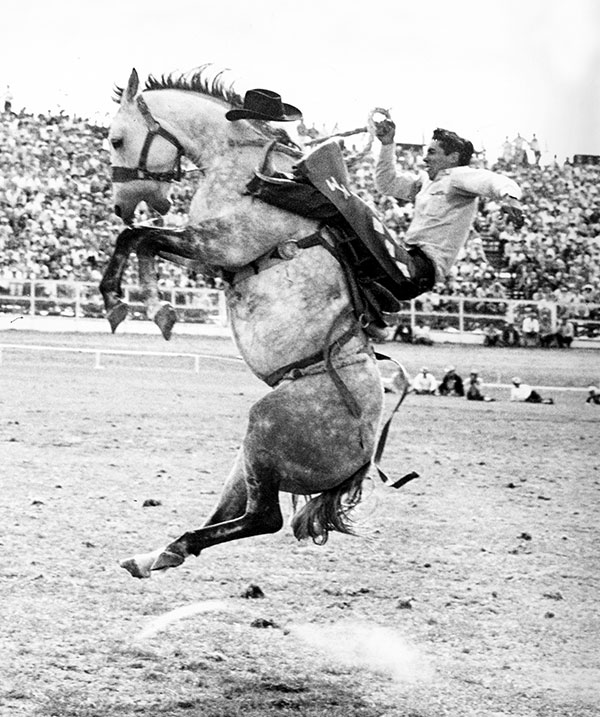

Kenny McLean, for example, was born in Okanagan Falls, B.C., in 1939. He began to rodeo at 17 and is still considered Canada’s greatest rodeo competitor, qualifying for the NFR nine times and winning 14 major Canadian titles. He was inducted into the Canadian, U.S., and Indian Rodeo Halls of Fame competing in saddle bronc, roping and steer wrestling. He won the NFR saddle bronc riding average title three times (1964, 1968 and 1971) and out of 77 rides at the NFR, he bucked off only five times. He won three Canadian saddle bronc championships and the World Saddle Bronc championship in 1962. He won the Linderman Award twice (1967, 1969), given annually to the cowboy who displays the highest level of excellence at both ends of the arena. He received one of our nation’s highest honours, the Order of Canada, in 1976. He passed away in 2002.

The very nature of the Canadian West shaped the character of the people to be highly adaptable to the vagaries of markets, weather and the opportunities they produced. In short, Westerners became known for being able to ride through a storm and make a buck doing it. This tough, independent nature contributed greatly to the unique nation that Canada is today.