Cattle and Gold

By 1844 President Polk had made U.S. ambitions in the far West clear with his slogan, “54° 40′ or fight.” It referred to a northern border adjustment between British and American territory in what is now B.C.

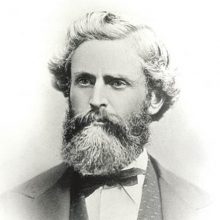

Vancouver Island had the best naval harbour north of San Francisco, coal deposits and timber. By the Oregon Treaty of 1846 Britain retained the Island in exchange for the Oregon territory that was flooded with American settlers in the 1840s. In response, Britain made Vancouver Island a crown colony in 1850. James Douglas, chief factor for the HBC in Victoria, became governor.

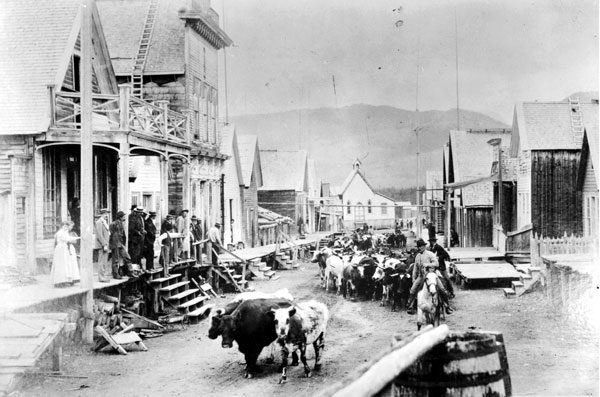

In 1856 Victoria’s population exploded with the Fraser River Gold Rush as Americans ventured north. Two U.S. power factions conflicted during the Fraser rush — the Law and Order party at Hills Bar and the Vigilance Committee at Yale, B.C. Douglas took control of the mainland where there was no government and imposed British law. He used an eccentric judge, Mathew Bailie Begbie, supported by the British Navy and Royal Engineers, to stamp out lawlessness and competition between the two power factions. Britain approved his actions after the fact, and made him governor of both the Island and the mainland.

The Cariboo Gold Rush swelled the town of Barkerville to 5,000 inhabitants. It was the largest town north of San Francisco and west of Chicago and they required dependable service routes. Douglas ordered the Royal Engineers to construct a 500-mile road up the Fraser Canyon from Yale to Barkerville at great expense to supply the gold fields and move troops if needed. Canada absorbing that debt would help promote B.C.’s joining Confederation. The road would be traversed by walkers, wagons, mule trains, horse packers and even camels to transport goods into the Cariboo. Like the CPR that followed it, the Cariboo Road was an incredible piece of engineering.

The gold rush era concentrated populations that required food, opening the Cariboo-Chilcotin area for cattle ranching to meet the demand as the cattlemen followed the gold seekers. The Gang Ranch was founded in 1863 by Thaddeus and Jerome Harper, two southern sympathizing brothers from West Virginia. They were strong opponents to U.S. annexation of British Columbia and even hatched a plot at the Confederate Hotel in Victoria to pirate the U.S. mint ship for the Confederate cause, but the war ended before it could be executed. They trailed Longhorn and Durham cattle in from Washington through the Okanagan to the Chilcotin and along their route other ranches would develop.

In the 1860s, Philipe Park built a ranch on the Bonaparte River in the South Cariboo and along with the Cherry Creek ranch and Hat Creek outfits supplied the lodging houses, such as 70 Mile House and 100 Mile House, on the Cariboo Road with beef. The Coldstream Ranch near Vernon was established in 1863 by Captain Charles Houghton and later owned by John Hamilton-Gordon, 1st Marquess of Aberdeen and Gov. General of Canada in 1893–98. In the Okanagan, Cornelius O’Keefe founded the O’Keefe Ranch in 1867 at the end of a wagon road that led into the Okanagan Valley. The climate was good for cattle, and for growing fruit and produce as well. There was an existing market in the various road houses along the Cariboo Road.

These ranches and road houses often became self-contained communities and hubs of development with post offices, blacksmiths, grist mills, churches, cemeteries, lodgings and stage stops. They increased in size with settlers and homesteaders who believed Confederation would produce an economic boom.

Not all attempts at driving cattle to gold rush markets were initially successful as evidenced by the unworkable Lillooet to Burrard Inlet cattle trail and Norman Lee’s failed attempt to drive 200 head to the Klondike from the Chilcotin. Persistence paid off however, and cattle were eventually driven over Yukon trails to the gold miners. Such entrepreneurs were very interested in the large markets potentially provided by Confederation with Canada and the railroad such a union promised to provide.

Burgeoning populations demanded dependable infrastructure like railroads to deliver products cementing Canadian Confederation with economic development. In the process, culture moved east and west as well as north and south. Today, Boulet cowboy boots are made in St. Tite, Que., where every year there is a popular rodeo and Western festival. The legendary cowboy artist and writer Will James, born Joseph Dufault in 1892 in St. Nazaire de Acton, Que., was lured to the West by its cowboy culture.

While the vagaries of history and geography would define Canada’s differences with the U.S., cowboy culture moving south to north with the cattle herds would link us. Beef products moved east to markets, and investment capital for ranching moved west. Gradually this became a reciprocal flow of products, culture and capital. The West had not only become a place in Canada but it had become a unique culture that moved along the very rails that serviced Confederation.