In 1931, at age 14, Harry Sheline chose cowboying as his trade. His parents tried homesteading in the Three Hills, Alta., area. His mother lived in a house tent the winter of 1905, and his father Andy spent the winter of 1906 in a house so thin it shook when the

wind blew. Harry was born in 1917 and in those days many homesteaders survived by selling hay to ranchers.

There was nothing about homesteading or making hay that appealed to Harry; he was drawn to horses and cattle. Harry looked over his options as the Great Depression settled in and decided he would ride for a living.

His first job was starting colts for Wib Edge on a ranch south of Bassano and he was expected to have them broke in a week. In winter the work changed. Harry hauled water using a tank wagon and team that he’d drive into the Bow River and then fill with buckets. He had to dig haystacks out from under the drifted snow, take care of the horses and fight through drifts to reach any trapped stock. Reality for a young cowboy in the

1930s had a particular edge to it.

When the time came to move on he went to work for the Ghost River Ranch, a 500-head cattle operation that he later managed. Harry again grew restless with the routine and decided to take a job breaking work horses near the old Cameron Ranch in the Woodhouse area.

In 1943, his brother George invited him to work on his ranch at Pincher Creek where he had rodeo stock. This caught Harry’s interest because he had been doing well riding bareback broncs using an old borrowed rigging.

It was a simple square steel handhold on leather and the rider sat behind rather than on top of the rigging. Harry also roped at the Calgary Stampede for a number of years, but his best event was steer decorating. Harry’s best time was at Ponoka in 1948 and he decorated a steer in four seconds. Harry rode bucking horses until he was 40, drawing his last horse, Miss Cache Creek in 1957 at Falklands, B.C. That was a mare that let him know it was time to retire from riding rough stock.

The Sheline brothers organized the Pincher Creek rodeo for five years but in 1949 they decided to move to B.C. and begin a cattle buying business on the suggestion of their dad, who was by then auctioneering at several B.C. stockyards. When his brother George was killed falling from a boxcar in the Kamloops stockyards Harry went to work for several ranches in the southern Cariboo. He would alternate his time between training horses in winter and working cattle in summer, often using these young horses on summer range to give them some experience.

Summer work in the South Cariboo hills was the usual; checking on cows and making sure that the bulls were circulating in the herd and not down in a shady creek somewhere. At roundup time some bulls would spread the cows out as fast as they could be bunched up. A rider could chase a herding bull away until his horse was sweating; only to gather the cows and have the bull spread them out again.

In mountain country cows tend to graze downhill and it was a constant job to keep pushing them back uphill. This continuous riding was hard on horses so Harry worked a horse one day and gave it two days off, since they would cover 35 to 40 miles a day checking the herd.

When he worked in the Similkameen area of B.C., the temperature sometimes dipped to -20 ºF on the fall drives down to Keremeos, but you couldn’t push the calves too fast or they would get separated, turn back and freeze to death. The most experienced cowboys rode point and drag to prevent this. Harry explained that, “You had to be really savvy about working cattle in that high country because you could end up chasing rather than gathering

cows and then you had better have one really good saddle horse. When you push cattle too hard in the mountains they can go places that will make your hair stand on end.”

Harry remembered feeding 475 head one winter after roundup for the Frolek Cattle Company. He chuckled when he said he had to “commute” to work, that is he had to ride five miles to the feed grounds and five miles back to his line cabin. The early spring meant more riding

because the cows wanted to eat anything green but they had to be kept away from jack pine trees since the turpentine in the needles could cause the cows to abort.

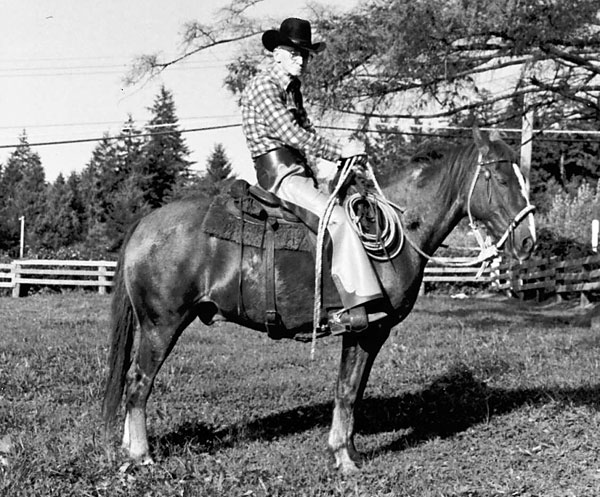

Harry was in his late 60s back in 1982 the last time I worked with him. The miles and the years had taken their toll by then so he didn’t ride much anymore. That spring we started a buckskin colt together and he taught me some of his old ways of working with horses. He said to me one day, “You know, ranching in those old days had its good points even though at the end of a day you sure knew that you had been working.” He reflected upon riding some good horses and bad broncs and he remembered days filled with wild range cows. He said, “There were some mighty long days in the saddle, but that was the only way I knew how to make a living. Anyway, no complaints and I figure it was a pretty good way of life.”

Harry Sheline passed away April 26, 1989 and is buried in Kamloops, B.C.