Canada’s New Beef Paradigm

May 20, 2003

It was the first Tuesday after the Victoria Day and across the country, Canadians were getting back to work after the long weekend. The distant promise of summer seemed real, and a carpet of new, green grass was spreading across cattle country in the West. And then everything changed.

That day, the government solemnly announced that BSE (Mad Cow Disease) had been discovered in a beef cow from Alberta. Ranchers were called to pick up their animals from auction because no one showed up to buy them.?Around the world, one market after another sealed their borders to Canadian beef. The most devastating closure was the United States, where 80 per cent of Canada’s beef and cattle exports would typically end up. The Canadian public rallied behind the industry, lining up to buy burgers in the aftermath in organized shows of support. Industry and government worked together to develop financial assistance programs, and to re-open markets as quickly as possible. Rural communities reached out to support their neighbours in any way they could?—?sharing chores, food, and shoulders to cry on.

Still, the suffering was immense. Family dynamics were forever changed. There were divorces, and young adults who found work in cities instead of at the family ranch. Families who had nurtured the same pastures for generations had no choice but to leave the land they loved, or to break it to seed it to grain. Cowboys looking forward to retirement went to town to find jobs pumping gas, just to hang onto their land and their cattle which the market said was now worth next to nothing. There were suicides, bankruptcies, lost dreams and broken hearts.

From the ashes of the crisis, a new Canadian cattle industry emerged. Some would say it came out stronger and wiser. Others might disagree, believing the heart and soul of the business was broken. But there was consensus on two things?—?the beef business had changed, and it had shrunk. In 2001, there were 122,066 farms with cattle, and by January 2012, there were fewer than 95,105 farms with either beef or dairy cattle. Many of the changes allowed Canada to become a global leader in beef production in areas such as animal health and welfare. The advances were seen as necessary to reopen foreign markets, and cattle producers were investing in technologies like radio frequency identification tags to track and trace individual animals.

Head-first, Canada’s remaining beef producers have plunged into this brave new world, only to face new perils. The U.S. and Canadian dollars were almost evenly matched, which decimated the profit margin that had made the north-south trade so profitable in the past. If the Canadian cowboy and the precious rangelands he rode were going to survive, trade paradigms were going to have to change.

November 13, 2013

The busy streets are lined with shiny cars, most of which came off the line within the last three to five years. The only vehicles that look older are the taxicabs, which are almost all Volkswagen Santanas made within the last decade. The frustrated driver behind the wheel of a BMW honks at the slow-moving traffic in front of him?—?a rickshaw carrying caged chickens. This is Shanghai, the economic epicentre of the new China.

Over the next three days, more than 90,000 people will attend the largest food trade show in the world, held in the heart of the newly-established Shanghai Free Trade Zone. The 28.78 square kilometre area is the only place in Mainland China where Facebook and other sites deemed politically sensitive can be accessed. It is a booming metropolis packed with modern architecture and five-star hotels. When it is a clear day, it is beautiful. When the air hangs heavy with smog, it is suffocating. But it is always moving. If Shanghai sleeps, it is in short naps between trade openings across time zones.

The FHC China trade show is where big boys of branding display trade booths as elaborate as Disney World rides. Campbell’s doesn’t have a booth?—?it has a giant can of soup, open on each end like a tunnel. Inside the red cylinder, buyers can travel through time as they examine advertisements and photographs documenting Campbell’s evolution. Heinz, Aunt Jemima, Spam?—?every flavour of the American dream is on display and for sale.

But the 580,000 square foot floor space doesn’t just house the best America has to offer?—?more than 45 countries have some skin in the game. They’re all after one thing?—?China’s emerging middle class and its new wealth. There are 1.35 billion people in China. That means for every one Canadian, there are 38 Chinese. There are 1.3 million millionaires in China right now, and just a hair fewer than 300,000 in Canada. Everyone wants a piece of the action, and Canada is no exception.

Usher in Canada Beef Incorporated (CBI), which was created in 2011 after Canada’s existing agencies responsible for beef research, marketing, and promotions were restructured into a new single and independent agency. Funded by cattle producers, their investment is leveraged to access development funds from the Canadian and Alberta governments. Canada Beef’s booth is in the meat building of the trade show. It is dwarfed by Australia, which is more of a destination than a booth, easily four times the size, which is indicative of their much-larger marketing budget. Despite its relative small stature, Canada Beef’s booth has impact. The look is modern, clean and clearly Canadian. A display case features bright red beef streaked with marbling so white that from a distance, it could be mistaken for roast-shaped candy canes. Two Chinese chefs are behind the grill, and an audience accumulates, drawn by sizzle and smell. The tender bites of beef are cooked just enough to brown the sides before they are stuck with Canadian flag toothpicks and distributed, sometimes to applause.

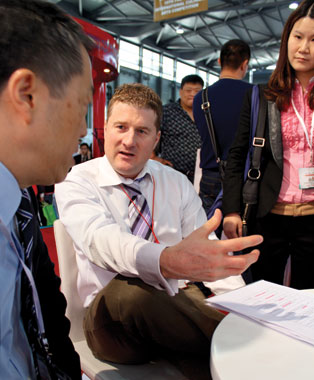

Behind the display case, the grill and the audience are cafe-style tables. CBI’s president, Rob Meijer and its chairman, Chuck Maclean, sit at one table with a potential buyer. This conversation is brief?—?the buyer asks only about price points and nothing about quality or how the beef is raised.

“You have to screen them out,” Meijer says. “Many are fly-by-night operators who only care about price points. That’s not who we are. You can’t deliver value like that.”

Meijer has led CBI?since its inception in 2011, and he’s all about building the brand to create value. In many ways, it’s a new way of thinking for the Canadian industry. When the U.S. dollar was high, Canada could deliver very attractive price points, and that’s often how business was done. But that strategy didn’t utilize Canadian beef’s strongest selling points?—?it’s among the best-tasting, most consistent beef in the world. It’s tender and grain-finished, and Canada’s health and safety standards are exceptional. It’s a premium product, the crème de la crème of the beef world, the Cadillac of steaks.

Alan Sarkin comes to the booth. He’s from New Zealand, but he’s been working in the Chinese market for years . He’s on a first-name basis with CBI’s Chinese staff members, and he smiles widely as he shakes hands with Meijer and Maclean. He’s in the process of sourcing beef directly from Canadian producers, and he deals only in gourmet. Price points don’t enter the conversation, and Sarkin is a straight-shooter.

“I’m a simple man. We focus on premium protein. I’m ready to commit to Canada, and to plant expansion to make it happen,” he said.

Meijer asks Sarkin why he wants Canadian beef, and what the brand stands for.

“The brand is Canada, and Canada is the brand. It represents quality, a pristine environment and wide-open spaces. It’s a cold weather beef?—?there’s a freshness associated with that,” Sarkin says.

In China, that perception is important. While only five per cent of China’s population consumes beef, that number is rising. And even at five per cent, that translates into more than 65 million people?—?nearly twice the entire Canadian population. That segment has money, and they want the fine things in life. They want what developed nations have and take for granted. They want fast cars, diamond rings and the latest fashions. They want expensive wine and gourmet cheeses. They don’t just want beef?—?they want the best beef. And most importantly, they want it to be clean and safe.

China’s economy is growing so fast, it’s almost cancerous. As the country opened to investment and opportunity, it was largely unregulated and when it was regulated, it was enforced ineffectively. That has meant an endless stream of food scares and scams. Recently, police seized 20,000 kg of fake beef, which was really pork that had been treated with chemicals and dyes to change its appearance.

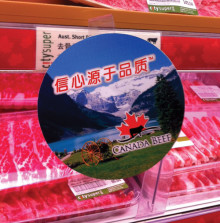

$38 per pound. Photo by Sheri Monk.

December 15, 2013

The holidays are fast-approaching and Canadians are busy buying turkeys and hams for the festivities. Most people aren’t spending a lot of time thinking about foreign markets, live cattle prices, or domestic beef consumption. But Canadian cattle producers are. They worry whether the cow herd has finally stopped shrinking, and what would become of Canada’s remaining natural grasslands if it hasn’t.

But Canada’s cowboys and cowgirls aren’t throwing in the towel just yet. Across the country, they’re volunteering to serve on industry organizations that work with, and through CBI. Some producers are adapting their herds for European and Asian market preferences. Cowboys with iPhones are tweeting about the health benefits of Canadian beef?—?at least that’s one chore that can be done from the saddle. The modern cowboy is a multi-tasker, and his survival depends on how well he can tell his story.

But it’s not just his tale to tell. It belongs to anyone who has loved a horse, from afar or from right up-close. It’s for all those who would rather watch a sunset than a television, or shake a hand rather than sign a paper. Sarkin is right. The brand is Canada, and Canada is the brand. And at the end of the day, we’re all riding for it.