Repatriating Canada’s Cowboy

|

|

Photo courtesy of Allan Jensen |

He arrived in from the East on a train, but rode out of the West on a bucking bronc. A greenhorn kid from Montreal, he was determined to become a cowboy on the open range of Alberta. His name was Ernest Dufault.

Two decades later he was lauded as a brilliant star of the vanishing old American West – a cowboy artist and author everyone knew as Will James. During the 1920s and ’30s, James wrote and illustrated more than 20 books about authentic cowboy life. His adoring public did not know he was a French Canadian who had learned the basics of ranch life in the Canadian West!

Dufault was born in a small village in southern Quebec in 1892 and the family moved to Montreal in 1901. Young Ernest was an intelligent, but average student who constantly sketched cowboys and horses with detail and accuracy.

|

|

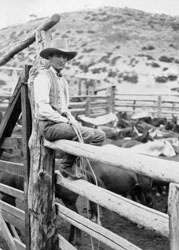

Rope Corral |

The lure of the West soon overwhelmed him and Dufault left Montreal after completing grade eight. With a bag of his mother’s cookies, a one-way ticket to Saskatchewan, and $10 in his pocket, the 15-year-old set out to find his dream. During the next few years he learned the “ropes” of the cowboy trade in both Saskatchewan and Alberta, eventually working as a wrangler and cowboy on some of the largest outfits of the time.

First-hand experiences of the prairies burned lasting images into Dufault’s imagination and memory during his remaining teenage years – vast dry expanses of grasslands, coulees, rolling hills and badlands. His apprenticeship taught him the rough lingo of the cowhands, the life of the bunkhouse, details of work around the corrals, the skills needed for wrangling high-spirited horses or night-herding skittish cattle, and the importance of a good horse – a 50-50 partner for a successful cowboy.

During his tenderfoot years on the prairies, Dufault adopted a series of aliases (more fitting for a “true cowboy”): Clint Jackson, Stonewall, William Roderick James and just plain Bill James. When he applied for a homestead near present-day Val Marie, Saskatchewan in June of 1911, he used the signature “W.R. James” (and listed his place of birth as Arizona!). After an incident involving a barroom shooting and a short jail term, he rode into the United States under the name Will James. Time for a brand new identity had come; he would “become” an American.

|

|

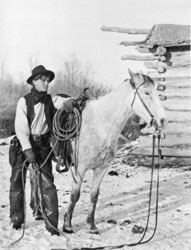

Photo by John Moir / Courtesy Glenbow Museum NA-862-1 |

James returned to Canada periodically to visit friends and seek work. The gawky adolescent, “not much good on a horse” had become a skilled cowboy and top-notch horse breaker.

After one visit to Medicine Hat in 1914, James fell in with a shady acquaintance in Nevada. They rustled a stray bunch of cattle and drove them to Utah. James was arrested and sentenced to 15 months in prison. For the prison records, he stated his birthplace as Montana!

Upon his release, Will James continued the life of a drifting cowboy. In Los Angeles, he found work as a cowboy and stuntman for the film industry during 1916.

In 1917, he travelled to the Calgary Stampede and met up with some old cowboy buddies. They attended rodeos all over southern Alberta, ending up in Medicine Hat. On their last night in the Hat, they put on a street show – singing and rope spinning. Someone suggested riding a bucking bronc down main street, but a police officer in the crowd stopped that!

By 1919 (following a brief stint in the U.S. Army), James decided his bronc-riding days were over. He enrolled in the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco, but found models, routine and repetition didn’t suit him and he left. However, he did submit some sketches to Sunset Magazine, and they appeared beginning with the January 1920 issue.

That year, James married 16-year-old Alice Conradt in Reno. They moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, where they met the Dean of Students of Yale University who offered James a scholarship. Again, he dropped out of school and came back to Nevada. Alice encouraged him to pursue his natural talents for storytelling and drawing and soon his fans included prominent artists like Charlie Russell.

|

|

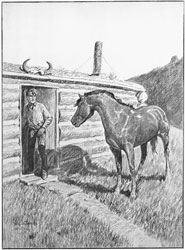

This carbon pencil drawing by James was published in the original 1926 edition of Smoky, the Cow Horse. The “cowboyese” language of James is apparent in the book’s caption that reads, “As he stepped out to get a bucket of water the morning sun throwed a shadow on the door.” Yellowstone Art Museum – Virginia Snook Collection, Billings, Montana. All rights reserved. Reproduced with permission from the Will James Art Company, Billings, Montana. |

James’s big break came in 1923, when Scribner’s Magazine began publishing his illustrated essays and stories. Scribner’s released his first book, Cowboys North and South, in 1924, the start of a steady stream of bestsellers like The Drifting Cowboy (1925), Smoky (1926) and Cow Country (1927). A literary sensation, they transcended the saloon brawls, six guns and shootouts – clichés of the Wild West. For the first time, an authentic cowboy wrote in his own vernacular, about the life and spirit of the cowboy, his observations flowing from pen and pencil. Scribner’s wisely published his prose the way James wrote it, in his inimitable “cowboyese,” errors of spelling, unique grammar and all. The New York Times commented, “He has an unvarnished but singularly salty and effective style – and when James draws a bucking horse, the horse isn’t merely bucking, he’s exploding”.

James’s novel, Smoky, the Cowhorse, went into 10 printings in four months, and was translated into Danish, Russian, Japanese, Yugoslavian, Swedish and Dutch. It received a Newbery Medal for children’s literature in 1927, and Hollywood made it into a film in 1933, 1945 and 1966.

James bought a ranch in Montana, but soon found he needed to write a book a year to finance his new lifestyle. In 1930 he wrote a fictionalized autobiography, Lone Cowboy: My Life Story. A big success, it was a Book-of-the-Month Club selection and made into a movie in 1934. However, the strain of keeping his real identity a secret became a nightmare. He begged his family to destroy any evidence that might reveal him as an impostor. He became an alcoholic. In the late 30s, he lost the ranch to creditors and Alice left him.

|

|

Smoky and the Snubbing Post |

By the early 1940s, his talent as an author and artist had worn thin. On September 3, 1942, Will James died alone in a Hollywood hospital, of cirrhosis of the liver and kidney failure. He was 50 years old.

Generations have grown up knowing little about Will James. Most of his books went out of print, his drawings and paintings largely ignored. But the Will James Society was formed in the U.S. in 1992, a publisher in Montana began reprinting his books in 1995, and biographies, documentaries, and art exhibitions have been produced.

Will James lived out his fantasy, part fact and part fiction. He lived the legend of the Old West and preserved its enduring myths of frontier and cowboy. A writer, artist, and folk hero, he is an icon of cowboy culture and heritage. Central to his legacy is that he really did become a cowboy. As Canadians, we need to repatriate Will James, his legend and his legacy as part of our cultural property and heritage.

Allan Jensen is an artist, educator, freelance curator and on the Advisory Board for the Will James Society. He is very involved in the repatriation of the Will James legacy and in October 2007, the first Canadian conference of the Society will be held in Medicine Hat, Alta.