Where Myth Meets Controversy

Photos by Jan Langsner

About 25 years ago RCMP, with lights flashing, raced their 4WDs into a grassy meadow to stop a young wrangler’s wild horse round-up. The officers apprehended the wrangler, Ken McLeod, impounded his saddle horses and equipment and ordered him to meet them the next day in the Lloydminster offices of Parks and Renewable Resources.

About 25 years ago RCMP, with lights flashing, raced their 4WDs into a grassy meadow to stop a young wrangler’s wild horse round-up. The officers apprehended the wrangler, Ken McLeod, impounded his saddle horses and equipment and ordered him to meet them the next day in the Lloydminster offices of Parks and Renewable Resources.

Those events in a meadow of the Bronson Provincial Forest made headlines in Lloydminster and, although largely buried by time, would prove to be representative of the continuing, unresolved issues today surrounding the status of wild horses in Western Canada.

In September, I accepted an invitation to meet Ken McLeod and view the wild horse herd in the Bronson Provincial Forest, northeast of Lloydminster, Saskatchewan. There should have been a postscript to the invitation: “Welcome to Controversy.”

Before I met Ken, I made a few phone calls to ‘interested parties’ and was told the horses were being shot each spring by hunters as bear bait; quad drivers chased the horses for…whatever reason; the horses were pests, not much different than a pack of wild dogs; and ranchers wanted the horses cleared out so more cattle could graze the area.

I was also told the horses, if properly managed, would bring a tourism boom to the area; that people, including ranchers, loved to see the horses running free; and the horses were part of our western heritage and not harming the environment.

Eventually I figured out why there are such conflicting points of view: when we discuss wild horses our culture is of two minds, the mythological and the scientific. While both views have valid premises, there is one point that nobody wants to touch: Who owns the wild horses?

I hoped Ken McLeod, 25 years after his run-in with the RCMP and the provincial officials, would have an answer to that question.

As I made the bumpy flight to Lloydminster, I thought about how wild horses are imbedded in the fundamentals of our North American mythology.

Wild horses represent the relief we seek from our daily routines. We’re tired of being bridled, saddled and worked hard. We’d like to abandon our obligations, clear the corral fence at full speed and gallop into eternity. The wild horse is our dream of freedom.

Wild horses represent the relief we seek from our daily routines. We’re tired of being bridled, saddled and worked hard. We’d like to abandon our obligations, clear the corral fence at full speed and gallop into eternity. The wild horse is our dream of freedom.

On the scientific side, biologists assert there are no truly wild horses in North America. Educated brains avoid the adjective ‘wild,’ choosing instead ‘feral’ or ‘free-ranging.’ The last wild horse, biologists will say, roamed the continent about eight thousand years ago, cause of death unknown. The feral horses of today are descendents of domesticated horses, beginning with those imported by the Spanish conquistadors in the 1500s. From these and subsequent imports, the feral herds emerged. By 1800 there were an estimated several million wild mustangs in North America.

Feral horses have no status in our wilderness landscape as the 1994 round-up of the herd at Canadian Forces Base Suffield demonstrated. There, the herd’s destruction of the watering holes, dunes and other wildlife habitat made it necessary for the horses to be completely removed in favour of the preservation of native species. If we were firm believers in survival of the fittest, we would have let the horses and pond frogs battle it out on their own.

Nor do feral horses have a place in our fringe area such as large grazing leases and forest reserves. There, feral horses are intruders, providing no economic benefit, especially when they compete for grass with cattle.

In between these scientific and mythological points of view is an argument that North America was the crucible of horse evolution and that, despite their disappearance from the continent millennia ago, feral horses are really a ‘re-introduced’ native species.

Another ‘in-between’ argument uses DNA testing to determine if horses have Spanish horse ancestry; the idea being that if a feral horse is determined to have Spanish ancestry, then those four or five hundred wild years are enough to remove the feral stigma from its family tree.

I admit that, by the time I arrived in Lloydminster, I had become so absorbed in the arguments for and against the preservation of wild horses and wild horse habitat that the actual viewing of the Bronson Forest herd had taken second place in my thoughts.

I admit that, by the time I arrived in Lloydminster, I had become so absorbed in the arguments for and against the preservation of wild horses and wild horse habitat that the actual viewing of the Bronson Forest herd had taken second place in my thoughts.

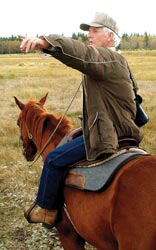

Fortunately, something unexpected happened while I was on horseback in the quiet of the Bronson Forest. Three unique people accompanied me: Ken McLeod; Jan Langsner, a Lloydminster photographer with B&R Photography; and Colleen Graham, of the Nothing Barred Ranch who had trailered in four good horses for us to ride that day. I knew each of them had opinions on the wild horse issue, but they kindly kept these to themselves.

Ken led us through Bronson’s dense willows and thin poplars, sighting horse tracks and manure along leaf-covered trails, creeks and in meadows, but never seeing a horse. By five that afternoon, our smiles were getting worn.

As we rode into a clearing near where we had parked the trailer, I was discouraged and doubted if I could write a credible story about animals I had never seen.

Then I glimpsed a bay with a bold white blaze trotting through the poplar shadows. Then a red roan froze, staring, wide-eyed, as we approached.

|

| Photo by Tyler Trafford |

Ken, familiar with the responses of the horses, recommended we ride closer. Within minutes the two young studs were swirling around our geldings, tails high, snorting, ears pricked, necks snaking, their dance filled with challenges. Ken urged us to maintain our positions and let this curious pair check us out.

For the next fifteen minutes I forgot all about science and mythology. I just watched and understood why, no matter which side of the argument one stands on, the grace of healthy wild horses has a fascination that is unmatched in our experiences.

An hour later we passed a harem of thirteen mostly sorrel and bay mares presided over by a mature, dark brown stud. Several ‘bachelors’ idled nearby. A few dozen cattle grazed amongst the horses. The scene was peaceful, almost idyllic. Jan photographed the herd while the rest of us relaxed in the evening sun.

Strangely, I didn’t dream that night.

The next morning I interviewed, on and off the record, those willing to share their thoughts on the Bronson Forest herd. The ranchers were careful in their comments, this being a close community. But, in general, they agreed that the wild horses were a pleasure to have, but cattle needed grass, too.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Most of the day was spent with Ken McLeod and, through his remarks, I began to understand the essence of the wild horse controversy.

Ken’s in his mid-fifties, grey-haired, thin, and wary. He is, figuratively, a wild horse himself. He’s led a rough and tumble independent existence. He lives in two old railway shacks, furnished only with necessities. His only attachment to technology is the video camera he has used to record hundreds of hours of wild horse footage.

In about 1980, at the request of a rancher who wanted the horses removed in favour of more grazing for cattle, Ken entered into what he considered to be a contract with Parks and Renewable Resources to capture the estimated 125 wild horses running on the 600 square miles of northern forest and meadows.

Ken captured four unbranded horses in his first round-up and took them into the Lloydminster stockyards where owners could make a claim before the horses were auctioned. Ken went to the provincial office, reported his results, and returned to the Bronson Forest to make another capture.

A larger herd was heading into his trap corral when the RCMP arrived. The next day, in the offices of Parks and Renewable Resources, the confusion over the ownership and responsibility for unbranded horses created a tense situation.

The round-up was halted while the government representatives who, acknowledging that Ken had permission to make the round-up, figured out what to do next. By this time, the community had begun to take sides in the mythological versus scientific debate. Eventually the Provincial Government sold the four horses and began a formal review of the need for a round-up.

Ken obtained another contract to round-up the horses in the mid-1980s, bringing 17 more into the stockyards. When the horses were auctioned, several ranchers and neighbours took up a collection to buy eleven of the horses and return them to the forest.

Ken bought six and began working to prove their trainability. He had good results but, the longer he worked with the horses, the more he thought about their former life. Within two years he couldn’t bring himself to sell them and he returned them to the forest.

From a horse trapper, Ken became a wild horse advocate, a believer in mythology. He formed the Western Wild Horse Association to which he would devote more money and time than he could spare, scientifically speaking.

“Who owns the wild horses?” I asked.

“They belong to all Canadians,” he answered. “When I spent time with the horses and saw how great they were, I thought we should do all we can to protect them as symbols of freedom.”

The Association folded when Ken ran out of money, energy and volunteers. But, last year, Ken McLeod met Ray Sproule, an extrovert with a historical and personal interest in the horses.

Ray’s family have been residents of the Bronson Lake area since the early 1900s when his great grandparents homesteaded in a nearby community. Ray has documents from his great grandmother referring to the “wildies” of the Bronson Forest.

While there is probably no definitive answer to the question of the herd’s origins, Ray has a theory that is as plausible as any. The herd, he believes, evolved from herds owned by the area’s Native tribes as far back as the late 1700s, breeding later with horses that either escaped or were released by ranchers and homesteaders.

Today the estimated 125 Bronson Lake horses have several recognizable characteristics. The majority are sorrels and bays, but occasionally there are palominos and greys. Any Appaloosa colouring is believed to be the legacy of an Appaloosa stud released into the herd decades ago.

Typically, the horses are between 12 and 14 hands, lightly built, and their heads have concave profiles. One rancher says their size is a particular adaptation to the harsh life of the Bronson Forest. Larger horses, he says, can’t survive the northern snow or the wolves.

“They are a breed of their own,” Ken McLeod claims.

Ray Sproule, the owner of B&R Photography, put together a tourism-based plan that Ken liked because it would keep the herd intact and in the park. After receiving favourable indications from local Native groups and government officials, he submitted a formal, multi-million dollar proposal to Saskatchewan Environment.

“With trained guides and responsible land and nature management, tourists would see the drama and natural way of life for the wild horses of Bronson Lake,” his proposal argued.

“Tourism and land management working hand in hand will be the success of this environment for the wild horses of Bronson Lake area.”

Saskatchewan Environment’s response focused on the horse’s legal status, rather than the viability of Ray’s proposal.

The “free-ranging horses in the Bronson Provincial Forest are considered an introduced, non-native species,” Rhys Beaulieu, the Saskatchewan Environment Wildlife Biologist for the area wrote back, adding that the department does not support special protection for the horses and has a plan to discourage the “introduction and persistence” of all potentially invasive species.

When questioned on the department’s priorities, Rhys said: “If I had to choose between moose and horses, I would pick moose. I am not going to manage other species to ensure horses stay there.”

If someone were to shoot a horse, he added, probably nothing would happen.

“They should just make sure no one owns the horse. We still have people claiming to own the horses.”

And, in that comment, I heard the fundamental issue in the controversy over wild horses: Who owns them? Are they feral, wild, free-ranging or are they owned, as Ken McLeod contends, by all Canadians?

Does their role in our cultural mythology entitle them to any status in our legal and scientific world?

Canadian Cowboy Country magazine is interested in your response to the question: Who owns the wild horses? Submit your response to editor@canadiancowboy.ca or write to our address listed on the masthead. Entries will be judged by the editorial staff and must be received before April 15. Two winners will receive a copy of The Story Of Blue Eye, a novel by Tyler Trafford. Winning responses will be printed in an upcoming issue of Canadian Cowboy Country.