True-life Adventures of Outfitter Chuck Hayward

Photos courtesy of Chuck Hayward Collection

The truck bounced painfully further into already remote backcountry. Shock absorbers groaned and the engine whine peculiar to four-wheel drives in low ratio was in full racing hum. Three men balanced on the truck’s bench seat as the vehicle bucked and heaved up the old lumber track, on her way to caching pack supplies for a long-planned – and in the year 2000 – centennial celebration ride to Fort Steele from the Spray Lakes along the Palliser Pass.

The truck bounced painfully further into already remote backcountry. Shock absorbers groaned and the engine whine peculiar to four-wheel drives in low ratio was in full racing hum. Three men balanced on the truck’s bench seat as the vehicle bucked and heaved up the old lumber track, on her way to caching pack supplies for a long-planned – and in the year 2000 – centennial celebration ride to Fort Steele from the Spray Lakes along the Palliser Pass.

Brian Smith firmly grasped the steering wheel. To his immediate right was Albertan ex-high profile politician turned lecturer and businessman Preston Manning with expedition leader Chuck Hayward on the window. Unbelievably another vehicle heaved into view, approaching and, as is backcountry etiquette, both drivers’ windows wound down for courtesies and introductions.

“Chuck Hayward,” the vehicle’s passengers exclaimed, “THE Chuck Hayward? Chuck Hayward the legend?” Their eyes shone, their enthusiasm wholehearted, focusing exclusively on Hayward’s compact figure. “Preston might as well not have existed,” remembers Warren Webber, another familiar of this backcountry adventurers elite inner circle of many years standing, “Preston would tell you this anecdote and you could hear the amusement in his voice every time. He said it was a new experience being quite so invisible.”

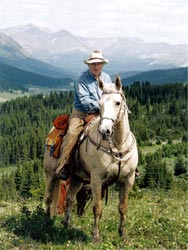

Chuck Hayward eases back today in his chair at his Millarville home he handcrafted years back into a hillside lush with poplar and aspen, and where now birdsong from an eccentric clock chimes the top of the hour. He says he is 80 but time surely lies. The eyes are clear and his mind acute on details; moving quickly to heave yet more photograph albums (they are all stunning and well chronicled) on to an already groaning table. It’s obvious he’s as supple as ever. Last year he led another expedition of friends through the wild reaches of the Willmore and this year he will have participated in Alberta’s centennial Suffield Ride.

Asked whether he ever gets stiff or creaky, he shoots a surprised look in my direction where I am scribbling. “No,” he says simply, “never.” He has promised to take me on “full-day rides, you’re OK with those?” to his secret trails and passes up in the Highwood and along the Great Divide and already my knees are fearing they might not live to tell the tale the next morning. I mention his surprised comment to his since-1968 colleague and fellow adventurer Dr Warren Webber, a partner at Okotoks Animal Clinic. “No,” he remarks thoughtfully, “I honestly don’t think Chuck ever really considers those kind of worries most people have about being cold and wet and hungry.”

Asked whether he ever gets stiff or creaky, he shoots a surprised look in my direction where I am scribbling. “No,” he says simply, “never.” He has promised to take me on “full-day rides, you’re OK with those?” to his secret trails and passes up in the Highwood and along the Great Divide and already my knees are fearing they might not live to tell the tale the next morning. I mention his surprised comment to his since-1968 colleague and fellow adventurer Dr Warren Webber, a partner at Okotoks Animal Clinic. “No,” he remarks thoughtfully, “I honestly don’t think Chuck ever really considers those kind of worries most people have about being cold and wet and hungry.”

Chuck Hayward in fact was born in the bush 40 miles north of Prince George and remarks quietly that “from an early age I knew how to survive in mountain living there.” His father “used to pack hides for the Great Northern Railway” but tragically died when Hayward, seventh of 14 children, was only 13. I ask his wife Laura, married to him forever since Dawson Creek days, if he’s changed over the years, and she says, dryly, no, nothing of any significance, with a fond smile as her knitting needles storm through a pattern. Chuck slides a careful glance in my direction and grins. “I had,” he remarks, “a degree of self-confidence, I thought I was better than most. Perhaps it was something to do with the family background, when you’re on your own when you’re 13, it makes you kind of resilient and self-sufficient.”

When, much later, we are wrapping up the interview I ask him if he ever felt he had been born in the wrong century and he grins again, leaning forward conspiratorially. “I think,” he remarks and his eyes twinkle, “I would have made quite a difference if I’d been born a hundred years sooner.” He pauses, a good storyteller waiting for a savoured mutual enjoyment from his audience. “My great-grandfather’s brother was on The Bounty and he was put in the longboat with Captain Bligh, and they went by open boat, 1,700 miles – an incredible journey.” He looks momentarily wistful, nostalgic perhaps for when adventures were to be had for the taking.

When, much later, we are wrapping up the interview I ask him if he ever felt he had been born in the wrong century and he grins again, leaning forward conspiratorially. “I think,” he remarks and his eyes twinkle, “I would have made quite a difference if I’d been born a hundred years sooner.” He pauses, a good storyteller waiting for a savoured mutual enjoyment from his audience. “My great-grandfather’s brother was on The Bounty and he was put in the longboat with Captain Bligh, and they went by open boat, 1,700 miles – an incredible journey.” He looks momentarily wistful, nostalgic perhaps for when adventures were to be had for the taking.

Hayward’s life began to change in 1968 with a visit to his dentist, a man who indirectly changed many other people’s lives with drastic consequences. He told his client, then a Calgary linesman (“those towers on 52nd Street, ” Chuck mentions enthusiastically and with a certain degree of pride, “I did those”) of an outfitting and guiding business up for sale in the North West Territories.

“The price was right,” exclaims Hayward, and it was the biggest area, 9,500 square miles and not a human living on any of it.” Enchanted, he bought the operation, South Nahanni Outfitters, sight unseen and immediately began to worry about a comment he’d overheard. “It seems,” he recalls, “that no one had ever hunted with horses up there and I thought, that sounds a bit unreasonable. You can get horses anywhere if you put your mind to it.”

Chuck bought the operation, he remembers, for $3,000. “I believe,” he remarks carefully, “last time it sold [he sold the business in ’75 after a guide, much loved and almost a second son, drowned in a river crossing accident] was somewhere in the region of a million plus.” Intrigued, I click onto the present-day website where a handsome young man and his blonde wife and child smile out with details of their version of an old outfitting operation. I click onto pages and pages of photographs and amongst the hunting trophies high up in snow-clad mountains, of Dall sheep and caribou and mountain goat, there is not one equestrian participant, not even a packhorse.

Not everyone, though, is insane enough to swim the Nahanni River in order to get to your base camp. Or, in the first attempts to either forge a trail there, or find one fashioned by migrating caribou, to persuade your pack string that climbing the highest mountain range around is an option, even if seemingly the most direct one. In later subsequent years, he would trailer his horses into the old tungsten CanTung mine area and then ride in, mostly along trails he’d cut “through thick muskeg and black birch. It was about 220 miles from CanTung. It got to taking around 12 days but that first time was quite a bit different because we went straight across the Broken Skull and up over the top of the mountains.” His hands gesture and I notice they all seem to have sharp serrated edges, these mountains.

High at altitude, he scouted but couldn’t find even a whisper of a game or caribou trail that would take him down. With the unbelievable luck that seems to have sat on his shoulder often, he encountered a helicopter flying through and whose pilot was the first of many to lay bets as to South Nahanni Outfitting’s survival prospects. Cadging the radio phone and still optimistic, Hayward suggested one of the local chopper pilots might like to consider airlifting his horses down one at a time in a cargo net.

High at altitude, he scouted but couldn’t find even a whisper of a game or caribou trail that would take him down. With the unbelievable luck that seems to have sat on his shoulder often, he encountered a helicopter flying through and whose pilot was the first of many to lay bets as to South Nahanni Outfitting’s survival prospects. Cadging the radio phone and still optimistic, Hayward suggested one of the local chopper pilots might like to consider airlifting his horses down one at a time in a cargo net.

Northern madness was obviously catching and by morning light “I picked the lightest horse I had, laid him flat on the ground and cut four holes in the cargo netting for his legs and feet. We looped the reins into the belly of the chopper and took him up,” Chuck explains as if this were as normal as having toast for breakfast. Already at 7,500 feet, an altitude where load and oxygen start to have disagreements, the pilot managed a couple of hundred feet before swinging back into land, the risk factor too high. What the horse had to say about the whole operation has yet to be translated into polite human vernacular.

“We zigzagged down the glacier after that,” he explains, “I went down the second one, made a bit of trail and I’ll never forget it, the horses went zzzzzz down the ice, sliding down. They’d go into the snowdrifts, we’d catch them again and start the whole process again.” With him, he had a young farm boy “who lived six miles away from me at home, which was the furthest he’d ever been before then.” Stuart Sinclair-Smith now lives (safely) in Okotoks but suffice it to say he was one of many backcountry outfitting guides of legendary toughness and resilience fashioned by Hayward’s can-do mentality.

“In later years we’d swim the Nahanni to get to base camp,” remarks Hayward, “we found a place where there was a little island halfway. You always swim horses downstream across a current. If you go upriver, if the current’s fast their feet lift right off the riverbed and they can flip completely over. I’ve ridden in racing creeks and almost had that happen, it was scary but I was lucky, I was riding,” he says nonchalantly, “a good horse.”

“One year we went across and had eight horses turn back mid-channel, the two guys riding drag weren’t quick enough and let them slip through. So,” he adds with storytelling relish, “we go upriver on foot, take our saddles and build a raft, took a couple of hours although I wasn’t worrying about those horses scooting anywhere. There were four cowboys, one on each corner to weigh down the structure.” He pauses carefully, “well, this chopper comes running upriver; he was about a hundred feet up and I heard him ease off the throttle although I didn’t know until later he’d taken a photograph, he couldn’t believe he was seeing four cowboys, on a raft, drifting down the Nahanni.”

“Getting out that first year,” he mentions, “was a bit memorable. I left it until the beginning of October and never did that again, we were always out by the middle of September after that.”

He goes on, sifting through thoughts. “Stuart had flown out, I didn’t have a good map and to Mackenzie was about 200 miles. Talk about cold water…in one day I crossed that river about seven or eight times, breathing in was easy, breathing out was the problem! I’d asked Stuart for the last barge of the season to stop and pick me up, and then I sat there for six days and six nights, waiting and beginning to wonder if he’d managed to get hold of them after all.”

“Finally the barge came, went right past, the current was so strong that first time. The gangplank was narrow and you could see through the metal mesh footing right through to the river. Some horses, ” he remarks mildly, “weren’t that keen but I took my saddle horse Sandy first. Sandy,” I said, “if you stay here you’re going to die…and she loaded up, no trouble at all! Actually she went up those stairs as if she was going into the barn at home. The rest pretty much followed after that, although there was one got a bit disturbed, he fell into the river the first time.”

He opens another photograph album, friends, hunters, countless smiling faces, float planes, the Chuckmobile that could wade across desperate muskeg that he built from a thousand spare parts, children grinning out from atop old fashioned packhorses. The Willmore, the Great Divide trails, high up in Kananaskis and beyond but it is to the north, to the Nahanni that, like many people who have lived and worked in that magical place, that his thoughts come home to.

“We submitted a story,” he finishes, and Laura glances up, laughing, a much shared and enjoyed private joke between them, “to Field & Stream that first year, of our adventures, and they wrote back, very apologetically, and said, we’re terribly sorry but we don’t publish fiction.”

Born an Easterner, transplanted to France and England, freelance writer Pam Asheton has since migrated steadily westwards and now lives NW of Cochrane which is, she says “close enough to satisfy a serious addiction to backcountry and high wild places.”