B.C.’s Skookum Indian Cowboys

Photos Courtesy of Historic O’Keefe Ranch

|

|

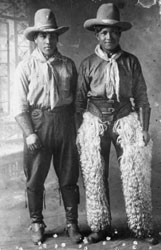

Native cowboys Andrew Tomar (L) and Christie Parker. By the late 1800s, Native cowboys realized the functionality of traditional cowboy trappings, and had fully adopted the gear and dress of their counterparts. |

The late summer day was hot and dry. The herd of cattle crossed the line into the new Crown Colony of British Columbia raising clouds of choking dust for those who drove them. The year was 1861.

The cattle, owned by Major John Thorpe were being driven to the goldfields of the Cariboo country to feed the thousands of miners that were flocking to the area. Through the dust could be seen the drovers (the term “cowboy” had not come into use yet) who were working for Thorpe. The crew consisted of Jack Splawn (whose account of the journey was included in his book Ka-mi-akin, the last hero of the Yakimas), Joe Evans, a mixed-breed named Paul, the Natives Cultus John, Ken-e-ho, and Ken-e-ho’s wife, who also drove cattle and cooked for the crew. What is remarkable is not the fact that about half the party were Natives but that this proportion of Native drovers was normal. Natives were a significant part of the labour force on the early cattle drives. A similar party led by Myron Brown in 1868 consisted of five whites and five Natives, “with all a rather agreeable crowd all things considered,” as Brown recorded. During the years 1858 to 1868 over 10,000 head of cattle were driven over the trails of British Columbia to the goldfields and Native drovers were a mainstay on most of the drives.

There was no question that the Native drovers were excellent horsemen. The horse had been introduced to the Pacific Northwest some 100 years before and the love affair between the Native people and the horse had begun. The culture of the interior Natives had changed forever. Within a few short years, every member of the tribe could ride as though they were born on horseback. It seemed inevitable that, when cattle were introduced to the Northwest, the Natives would find an occupation that suited not only their abilities as horsemen but also the way of life.

You would think that the same would apply east of the Rockies, where the Natives of the northern plains were superb horsemen. But, as we can see from the earliest records, the use of Native cowboys in the ranching industry was significantly different on the eastern side of the Rockies. In British Columbia the Native cowboys were the backbone of ranch labour from the very beginning but in Alberta and Saskatchewan they were slow to be accepted by the industry. Why was this so? What factors in British Columbia made the Native cowboy such an integral part of the early ranching industry when the same was not the case east of the Rockies?

|

|

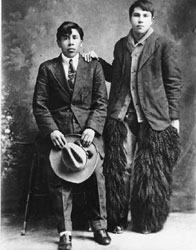

Hans Richter was the son of early B.C. rancher, Frank Richter, and his Similkameen Native wife, Lucy. He was one of the area’s best horsemen and a rodeo pick-up man. |

First of all, the frenzy for gold meant that the labour force for driving the cattle was limited, most available men preferring to try their luck in gold mining. The influx of thousands of young men to the Fraser River and beyond, searching for gold, required food to be supplied to the goldfields and there was a surplus of beef cattle in Oregon. For the cattlemen of Oregon, the Native population was a source of reliable and affordable labour to get their cattle to the new market in British Columbia. It seemed only natural that young Native men would be chosen to drive cattle.

Perhaps the most significant difference between the two sides of the mountains was that, in the Northwest, language was not a handicap as it was to be east of the Rockies. Almost all of the Natives and whites spoke the trade language, Chinook, which had developed during fur trade times in the Pacific Northwest. This made basic communication possible. So if a trail boss was to say “Mamook kishkish moosmoos kah cole chako” everyone in his party, whether Native, European or for that matter Chinese, would know he meant “Drive the cattle north.” Chinook was the common language of the different races in British Columbia right up to the early 1900s. In fact, it was said that, “Early British Columbia cowboys were masters of three languages – English, Chinook and profane.”

This bridging of the language barrier was the most important factor in the acceptance of the Natives as drovers. The ability to communicate has the effect of breaking down many of the prejudices that so often divide the races. With the acceptance that came from easy communication and the sometimes grudging admission that the Natives were excellent cowboys, the tension between the Native people and the white intruders was much less than it would be on the east side of the Rockies. This acceptance found another form in the predominantly male frontier. Many of the earliest ranchers in British Columbia married Native women and the children of these marriages worked on the ranches of the interior. These children were among the best working cowboys in British Columbia as the ranching industry grew and prospered among the bunch grass ranges of the interior.

|

|

Native cowboy Charlie Still’s winning ride on Steamboat at the Kelowna Rodeo around 1910. In those days horses were ridden to a standstill, so rides could take up to several minutes |

As “civilization” came to the British Columbia interior, the acceptance of the Native and mixed-blood people deteriorated, especially in the cities and towns. They were looked down upon and treated as inferior. But this was seldom the case in the ranching community, where the Native cowboys were always part of the scene. Throughout ranching country, Native cowboys worked alongside young men from all over the world and, most often, the Natives were the acknowledged experts. Working cowboys like Antoine Allen, who came north with the Harper Brothers in the 1860s and was still driving cattle in 1913 or Okanagan Native, Joseph George (Susap)[his native name] who cowboyed and packed for ranches in the South Okanagan, were acknowledged as the best of their kind. Many mixed blood cowboys rose to be leaders in the ranching community. This was the case with Joe Coutlee, who was cow boss of the great Douglas Lake Ranch for 48 years. The same qualities could be found in the early rodeo world where horse contractor, Hans Richter, was acknowledged as one of the best pick-up men in early B.C. rodeo. His lead was followed by Louis Bates and Gus Gottfriedson, who became horse contractors in the 1940s and 1950s, and rodeo cowboys like Dave Perry and Louie Bates who excelled in the rough world of rodeo. Their tradition of excellence has continued in such modern day heroes as Kenny McLean, the great bronc rider. Even today, a visit to the cow camps and big ranches of the B.C. interior will show that Native cowboys are still a vital part of the ranching community.

|

|

Okanagan Native cowboys Able Antoine (L) and Joe Marchand. Woolly chaps like the ones worn by Joe were very popular with Native cowboys in the early 1900s. |

Ken Mather has been involved in heritage writing, interpretation and management for the past thirty-three years. He is the author of Buckaroos and Mudpups – The Early Days of Ranching in British Columbia.