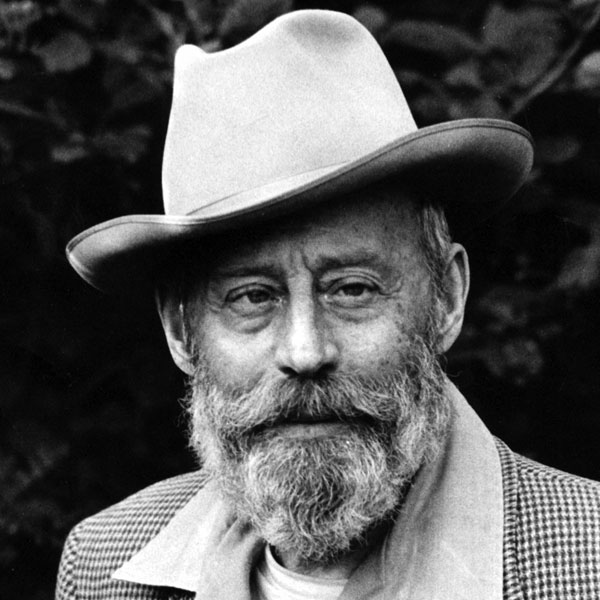

With his books, poems and artwork, R.D. Symons was to the Canadian West what Charles M. Russell was to the West of the United States.

Born in Sussex England in 1898 he came to Maple Creek, Sask., at the age of 16 to learn to cowboy. He acquired his skills in the Cypress Hills and the Box Elder ranch area. He homesteaded in Arm River Valley and ranched in the Peace River country north of Fort St. John.

In his most popular book, Where the Wagon Led, he compiled some poignant incidents concerning cowboy life north of the Montana border, shattering the myth that the Canadian West was peaceful and uneventful.

The winter of 1886–87 had been disastrous but after the winter of 1906, Canadian ranching had changed forever. The lead grey sky that had ushered in the first of that season’s blue “northers” had settled over the rangeland with an icy death grip. The 1906 big freeze would leave many ranches with less than half of their herds alive by spring.

Many of the herds were owned by Eastern businessmen who would never feel the penetrating talons of a blizzard working through a snow-stiffened slicker or have to push an exhausted horse through five-foot drifts checking for strays.

For the common cowboy, that winter was a losing battle with a relentless opponent. It was a winter when survival meant wearing buffalo coats over moose-hide jackets and for the lucky cowboys, angora chaps or woolies to keep their legs from freezing. The less affluent wrapped their limbs and feet in newspaper for insulation. Frostbite was common and time was measured in the cords of wood consumed by the bunkhouse stove.

Some years later Symons had a taste of the 1906 winter. He rode close to a cow, standing upright in a snowdrift, frozen solid and staring with round eyes that he described, “as hard and glassy as marbles.” It was common to shoot cattle that were frostbitten, blind with frozen eyes or with tails as stiff as broom handles. They were sorrowful sights with strips of hide missing and their ears, horns and foreheads fused together in a mass of ice.

When the thaw finally came the remainder of the herd wasn’t worth much, “a bunch of bones wrapped up in leather,” Russell once quipped. Dead cows hanging in the treetops attested to the depth of snow in the coulees.

The cattlemen learned from the killer winters that the herds would have to be controlled and fed in winter. More and more grazing land was fenced, a signal that the days of open range were passing and the barbwire had come to stay.

Much of what Symons learned about cowboying came from Lee Blackwell. He was a top hand with the Matador Cattle Co. and later worked for Alex Gow, a leather tough old Orkneyman who had worked for the police at Fort Walsh. Among other skills, Blackwell taught Symons that it was always best to travel well-armed for as he said, not all of the rustlers in Canada were dead.

Symons remembered an ornery old rustler named Geisner who had nested in the Sand Hills. He ran a few head of livestock and under the cover of a country store, ran a roost for stock thieves. His corrals were always in excellent repair for the small number of stock he ran and there was lots of evidence of fresh branding fires beside a very stout squeeze gate. There was no grass growing in these corrals, although they were always empty in the daylight, and the ground was chewed up to the depth of about six inches. They appeared to be in constant use even when legitimate ranchers had their stock out on the range.

Symons rode up to Geisner’s gate one day when two riders by the names of Preston and Myers were cutting out some young stock from a bunch that had been gelded but not branded. That was unusual because both jobs were usually done at the same time. Symons went to the local NWMP office to mention what he had seen at Geisner’s ranch and he noticed a wanted poster on charges of horse stealing on one of the riders, Chinook Tony Mistral alias Jake Myers.

It seems Myers had been stealing young horses in Saskatchewan and driving them south to Montana. When the Mounties began to close in, Myers rode hard and disappeared somewhere into the States.

One spring morning Symons was startled by something that could only be described as a phantom. Weak from starvation, unable to walk properly and gaunt in appearance, there appeared a horse known as Old Fox. The broken hobbles still hung about his ankles, where they had caused fly-crusted sores to form.

Symons and the other cowboys could see from the XA brand that the animal belonged to their ranch and had somehow made it home. This was the horse that Myers had escaped on and by the look of him, he had travelled from the Bear Paws and the Missouri Breaks south of the line.

It was assumed by the police that something happened to Myers probably while his horse was saddled but still hobbled. Maybe he met his end as a result of justice from a Winchester

or Colt. While trying to return home, Old Fox had been forced to winter wearing those hobbles, a saddle that he probably kicked off and a bridle that had cut his tongue severely. One look at the horse and the fact that Myers was missing evaporated any glamorous thoughts that the younger cowboys might have had about the outlaw way of life.

Symons died in 1973 leaving behind stories filled with characters and incidents both happy and harsh that were as numerous as the rolling hills that spawned them. He placed the highest of values upon the time he spent as a cowboy and upon the freedom that a life in the saddle offered in the Canadian West.

My hero! I live just a few miles from where R.D. lived when he worked for Scotty Gow 1904 on the Box Elder Ranch in the Cypress Hills. He was Park Ranger just a few miles down Battle Creek Valley in the early 40s. His gift of writing and painting are priceless. He has enriched my life, helping me appreciate what our forefathers worked so hard for when they settled here in the Cypress Hills.